At the Venice Biennale, the Netherlands has invited a plantation workers' art collective from the Democratic Republic of the Congo to fill its pavilion. The International Celebration of Blasphemy and The Sacred includes clay effigies and palm oil on the walls.Matteo de Mayda/Courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

There are times in Venice when it seems as if the mighty Biennale will collapse under the weight of its own contradictions. Conceived in an age of Eurocentric nationalism, it must now contend with postcolonialism and postnationalism.

This is the place where the elite of the Euro-American art world must consider what it’s like to be an Algerian migrant living on €30 ($44) a day in unfeeling France, or a gay man making erotic art in puritanical China. It’s the place where activists feel required to hold their pro-Palestinian demonstration even though Israeli artist Ruth Patir has announced her show will remain closed until there is a ceasefire and hostage release in Gaza.

This year, the Netherlands found an easy fix. In the Giardini, the large park at the eastern end of the Grand Canal that plays host to the Biennale, the Dutch handed their national pavilion to a plantation workers’ art collective from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The artists have dripped palm oil over the white walls and filled the room with pointed statements to Western consumers about what it feels like to be on the production end of resource extraction. “No white cube can claim to be decolonized as long as the plantations are not,” they wrote.

Meanwhile, the Russians, banned since they invaded Ukraine, have lent their pavilion to the Bolivians for a show of Latin American artists said to be united by Indigenous origins and a desire to live in harmony with nature. Skeptics suspect the Russians are more interested in Bolivia’s lithium reserves than its Indigenous artists or their environmental aspirations.

This is the context in which Brazilian curator Adriano Pedrosa dedicates this year’s massive group show, a fixture of the Biennale, to overturning the narratives of Western art. His choice to include a lot of 20th-century South American art doesn’t always convince, but at an event that can turn into an unseemly jostle to discover the hottest new thing, his stress on the predecessor, the outsider and even the anonymous is welcome.

Pedrosa’s chosen theme is Foreigners Everywhere. The phrase, coined in Italian by an anti-racist collective in Turin in the 2000s, is displayed at the Biennale on neon signs in multiple languages. It is supposed to evoke human migration and otherness, not xenophobic paranoia. (Perhaps Strangers Everywhere would have been a better translation.)

Within that broad theme of the outsider, Pedrosa has found several fertile areas, including the work of queer artists, textiles by women and familial artistic practices in traditional cultures.

But first he has to get something off his chest: The main pavilion at the Giardini features a mini retrospective of South American abstraction from the 1950s to 1970s. Highlighting vibrant colours and softer lines, this section argues that artists such as Ione Saldanha, Olga de Amaral and Rubem Valentim, largely unknown to global audiences, took modernism in different directions than their northern peers. There is some lovely work here and some surprisingly weak, including a piece by Mozambique artist Bertina Lopes that’s painfully derivative of Picasso’s Guernica. Generally the display seems beside the point, arguments about modernism being a ship that has long since sailed.

Similarly, over at Arsenale, the repurposed shipyard to which the Biennale expanded in 1999, Pedrosa tips his hat to his hosts and includes an odd section about expat Italian artists, also featuring 20th-century work. There’s the occasional find – Lidy Prati’s rhythmic repetition of small geometric shapes from the 1940s – and some embarrassments, including two artists who painted exoticized images of Thai and Balinese dancers. The thorny issues of appropriation and authenticity are not on Pedrosa’s list.

On the other hand, depictions of queer experience are. At the Giardini, the display juxtaposes the retro-looking but recent paintings of gay domestic life by American artist Louis Fratino – An Argument shows two naked men sleeping separately – with a surprising precedent from India: Bhupen Khakhar’s 1985 painting of three fisherman, one wearing only a vest while holding a strategically placed fish.

An Argument (2021) by U.S. artist Louis Fratino, at the 'Foreigners Everywhere' exhibition at the 60th Venice Biennale.Matteo de Mayda/Louis Fratino/David Bolger Collection/Venice Biennale

Don’t Worry, mom is spinning thread in the next room (A love scene when high school student is at home writing homework), 2019, papercut with water-based dye and Chinese pigments on Xuan paper, by artist Xiyadie, at the Venice Biennale.andrea avezzu/Xiyadie/Venice Biennale

This is tame compared with the work of the Chinese artist Xiyadie, which includes painful symbols of coming out but also images of men fellating each other. The shock is his medium: traditional Chinese paper cuts, a practice so firmly associated with banal images of carp or flowers that one can barely believe one’s eyes.

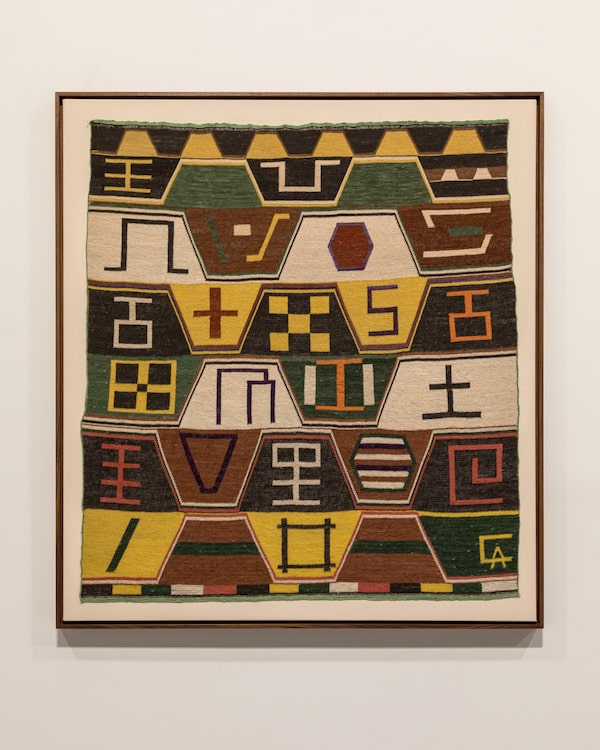

If gay artists do well here, so do female artists, both current and of the recent past. The rooms at the Arsenale are filled with intriguing textiles, including naturally dyed and loosely woven work made of the fibrous chaguar plant by Indigenous artist Claudia Alarcon and the collective Silat, both from Argentina. From a distance, these pieces look like abstract paintings. There is also fantastical botanical imagery by self-taught Moravian collage artist Anna Zemankova in the 1980s, and arpilleras, anonymous scenes of everyday life in Chile quilted during the dark days of the Pinochet dictatorship.

Claudia Alarcon and Silat. Textile woven from the chaguar plant.MARCO ZORZANELLO/Venice Biennale

Anna Zemankova, Untitled, 1980 ca., satin collage, fabric colour and ballpoint pen on paper.MARCO ZORZANELLO/Venice Biennale

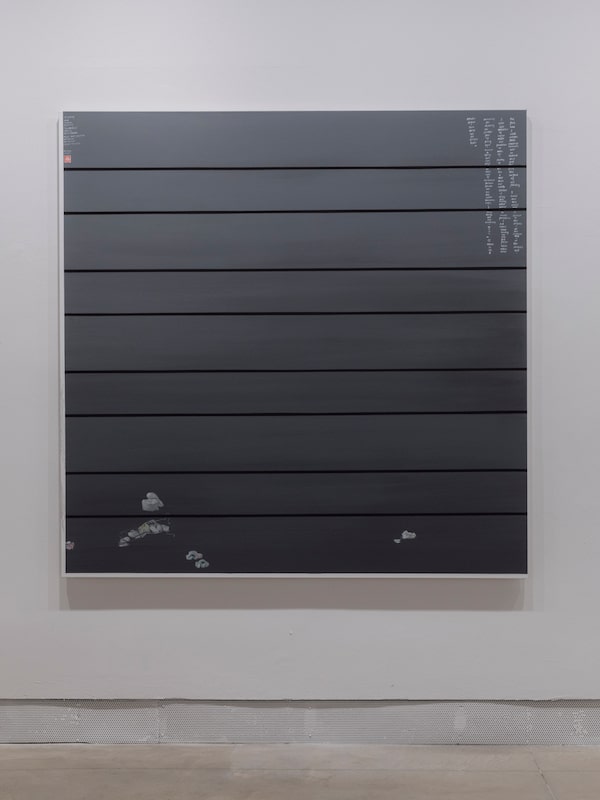

Back at the Giardini, there are convincing rooms filled with works by well-recognized contemporary female professionals. These include monochromatic paintings of historic photos by Italian artist Giulia Andreani; compelling black grid paintings by Filipina artist Maria Taniguchi; and Evelyn Taocheng Wang’s witty reproductions of the rigorous grids of abstractionist Agnes Martin. (Wang, a Chinese artist who lives in the Netherlands, adds little tweaks of representational content.)

Makeup Remover Cotton Pads and Imitation of Agnes Martin, by Evelyn Taocheng Wang, in the Venice Biennale exhibition 'Foreigners Everywhere.'Matteo de Mayda/Evelyn-Taocheng-Wang/Venice Biennale

And yet, another theme that emerges is the obsessive surface produced by the outsider artist. The Giardini show includes two notable examples: the repeating female faces of early 20th-century British spiritualist Madge Gill and, from a similar period, the exuberant images of costumed figures and flowers created by Swiss artist and lifelong psychiatric patient Aloise Corbaz.

Masonic Funeral (1968) by Sénèque Obin in 'Foreigners Everywhere' exhibition.Matteo de Mayda/El Museo del Barrio, New York/Venice Biennale

This horror vacui, or fear of blank space, dominates works on display by other self-taught artists, alongside compulsive recording of daily life or historic events and attention to illustrative detail. In the 1950s and 1960s, Seneque Obin scrupulously recorded important episodes in Haitian life just as the Mayan artist Rosa Elena Curruchich would do in Guatemala in the 1980s and Aboriginal artist Marlene Gilson does today as she exposes Australian colonial history. The Colombian Indigenous artists Abel Rodriguez and Aycoobo (Wilson Rodriguez), whose precise botanical and spiritual imagery has been a highlight at the Toronto Biennial, are also featured here.

They are father and son and the show also includes work by Obin’s brother Philomé and one piece by Curruchich’s famed grandfather Andres, revealing how art in a traditional society can be a family trade rather than the preserve of a single genius.

Many of the artistic families included here are Indigenous. South American Indigenous people are well represented by the Brazilian curator, but Australian and New Zealand artists also come across strongly in a year where Aboriginal artist Archie Moore won the Golden Lion for chalking up a 65,000-year-old family tree on the walls of the Australian pavilion. At the Arsenale, Naminapu Maymuru-White’s bark paintings echo other women’s work in textiles, while the Maori collective Mataaho (which won the Golden Lion within the group show) has woven a canopy of polyester strapping over the entrance.

A few Indigenous artists from the United States are represented, including Kay WalkingStick, who adds Cherokee motifs to Southwestern landscapes, but sadly Indigenous art from Canada is invisible.

It might seem odd to consider Indigenous peoples as Foreigners Everywhere given that they were here first, but perhaps the point is that they are made outsiders in their own lands. Elsewhere, one of the strongest themes is, naturally, migration. It’s addressed by Moroccan-French artist Bouchra Khalili in her Mapping Journey Project of 2008-11, where she trains her camera on maps as migrants trace their torturous routes with marker. An Algerian fisherman sails his boat to Sardinia and eventually finds himself in France making a pittance delivering flyers door to door.

And yet, Khalili also turns these paths into something more obviously esthetic, in silkscreen prints that map them as white constellations on indigo backgrounds. The insistence on story, the impulse to create beauty – well, that’s art, wherever or whoever it may come from.

Foreigners Everywhere at the Venice Biennale continues to Nov. 24.