Some dancers take more than a decade to rise through the ranks of a professional ballet company. Others, such as the New Zealand-born Harrison James, manage a swift ascension in three quick seasons.

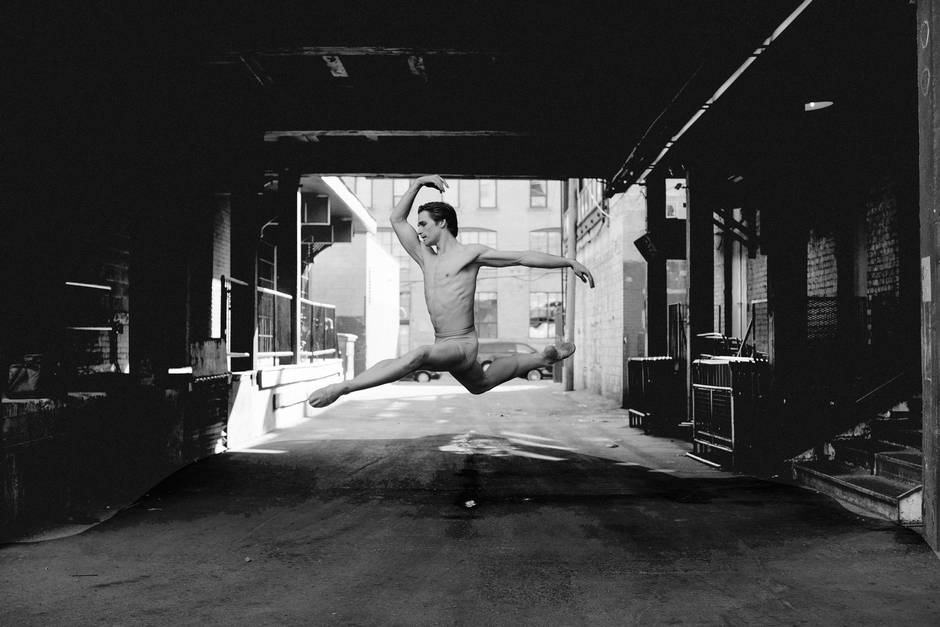

When the National Ballet of Canada opens its four-night run of Christopher Wheeldon’s The Winter’s Tale at New York’s Lincoln Center this weekend, the 25-year-old James will be the company’s newest and youngest principal dancer. An elegant classicist with striking poise and emotional depth, James was virtually unknown when he joined the National’s corps de ballet in 2013.

Bad luck during his first year prolonged this obscurity; a tear to the FHL tendon in his foot left him out of commission for most of the season. But things started to change in 2014, when the company found itself unexpectedly short on male principals for Kenneth MacMillan’s Manon. James rose to the challenge, making an impressive debut as Des Grieux, the lovelorn male lead, opposite seasoned principal dancer Jillian Vanstone.

Despite still being in the corps, James spent the rest of the 2014-15 season working like a dancer of much higher rank. Manon was followed by a turn as the male lead in Wheeldon’s Carousel (A Dance), then the opening-night slot as Prince Florimund in The Sleeping Beauty. It was in this 19th-century favourite that James proved his mettle as a classicist. Technically, the role gave him the opportunity to showcase his grounded and lyrical adagio – slower choreography that’s heavy on arabesques, developpés and luxurious port de bras. Artistically, it let him reveal his charge and sensitivity as a performer. James can do melancholy without getting maudlin. His charm always comes with a bolt of seriousness, a flash of verve.

Among the 10 homegrown principal dancers at the National Ballet of Canada (i.e., those who didn’t establish their careers first at other companies), the average time span from joining the company to promotion to principal is about eight years. Of course, the vast majority of company members never make it to the top at all. Like most hierarchies, traditional ballet companies rely on a bottom-heavy pyramid, with many dancers spending 10- to 15-year careers performing the background choreography of the corps de ballet.

But extraordinary talent (and good timing) can prove an exception to the common narrative. Young stars have soared through the company system at a meteoric rate, suggesting that maturity, ability and presence can stand in for hard hours of experience clocked on stage. There’s precedent for this kind of speedy ascension among some of the National Ballet’s big names of former decades: Veronica Tennant joined the company as a principal dancer at 18 (1964); Frank Augustyn was promoted to principal at 19 (1972); Karen Kain became a principal at 20 (1971).

In June, 2015, when as artistic director, Kain made her annual announcement of promotions, she rewarded James’s precociously strong work with a move straight from the corps to first soloist, skipping over the second-soloist rank. Last month, in her 2016 announcement, she made him the company’s only new principal dancer.

If you’ve seen James’s classical work on stage – and if you’re an opening-night subscriber, you will have been lucky enough to have seen it many times – his quick rise will come as no surprise. Imagine the most dashing and magnanimous princes of 19th-century literature and you’ll conjure an idea of his magnetic presence as a performer.

I sat down with James just before the company left for New York, where he’ll be reprising the role of Polixenes. In person, he looks like a Disney hero come to life, with blue eyes that are too gentle to call piercing, a dazzling smile and a sweep of cropped blond hair. He’s as modest as he is talented, claiming that his real strength lies in good partnering. “I love telling a story with someone. I’ve never been a showman in terms of my dance ability. I can’t do a thousand pirouettes, I don’t have this crazy jump, I can’t do amazing tricks. I think I’m consistent and clean,” he says, then laughs a little self-consciously.

James grew up with three siblings in a small community on New Zealand’s Kapiti Coast, an hour north of the capital city, Wellington. His mother suggested dance classes when she saw that her five-year-old couldn’t sit still, and James took immediately to the structure and rigour of ballet. “I have a mathematical kind of mind,” he explains. At 15, he enrolled in the full-time program at the New Zealand School of Dance, then moved to California two years later to begin the professional trainee program at the San Francisco Ballet School. Upon completion, the renowned San Francisco Ballet offered him a place in their corps but, unable to get the necessary work papers, James accepted a contract with the Royal Winnipeg Ballet instead.

Beginning his career at a smaller and less-competitive company proved a savvy move. By his second season, James had been promoted to second soloist and was already dancing lead roles, including the title role in choreographer Mark Godden’s Svengali (in fact, the part was created on James). James was promoted midseason to first soloist and ended the year dancing one of the most important roles in the classical canon: Albrecht in Giselle.

But rather than get comfortable in Winnipeg, James was hankering to travel and garner more personal experience. He accepted a contract for 2012-13 with the Béjart Ballet in Lausanne, Switzerland, and spent the year touring with the company. While he relished the exposure to European dance and Béjart’s uniquely theatrical repertoire, he found himself looking back over his shoulder at Canada. There’d been a romance in Winnipeg that he wanted to return to, and Toronto looked like the right compromise for the couple. So James set his sights on joining the National Ballet.

When Kain hired James in August of 2013, she was confident of his charisma and potential, but didn’t anticipate how quickly he’d climb the company ladder. “He became our hero,” she says, citing how he stepped up to the challenge of demanding classical repertoire when they were short on leading men. Most recently, this meant dancing Albrecht with three different Giselles, a feat of dexterity that would be difficult for a veteran. “I started to notice his capacity for hard work – his will and desire. The longer he’s been here, the more I’ve seen him want this for himself. I see a real commitment now.”

The past season has been a whirlwind for James, with masterful performances as the naive, starry-eyed male lead in La Sylphide and Albrecht in Giselle, both falling under the older rubric he so excels at. A self-professed romantic, James likes to spend his downtime at coffee shops in Toronto’s King Street West neighbourhood, writing in his journal or reading science fiction. After dancing Polixenes in New York, he’s looking forward to a season that seems tailor-made for his classical bent, flush with pinnacle ballets that will let him dig deep into character and emotion.

Is there a particular role he has his eyes on?

“Lensky,” he says. He’s referring to the wide-eyed, dreamy poet in John Cranko’s ballet Onegin, a gem in the company’s repertoire that’s scheduled for November. “I’m really a lot like Lensky.”

The Winter’s Tale is presented at Lincoln Center in New York through July 31 (ballet.ca).