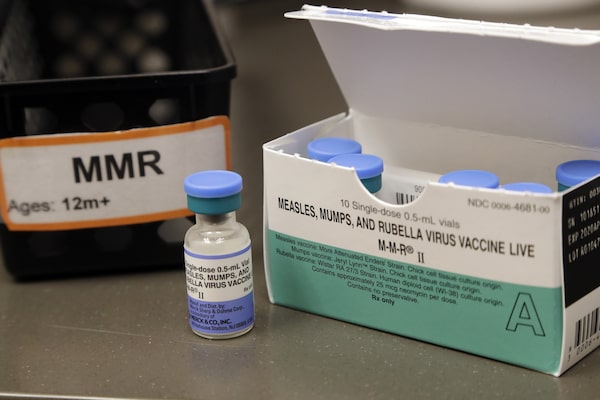

A dose of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine is displayed at the Neighborcare Health clinics at Vashon Island High School in Vashon Island, Wash., on May 15, 2019. Although measles is no longer endemic in Canada, a significant swath of the pediatric population is at risk because of low vaccination rates.Elaine Thompson/The Associated Press

A surge in global measles cases means Canada must take immediate action to improve faltering vaccination rates, according to pediatric infectious disease and immunization experts.

The World Health Organization issued an alert in December about what it described as an “alarming” rise in measles cases in Europe. The continent saw more than 30,000 cases in 2023, compared with 941 in 2022.

And earlier this month, health authorities in the United Kingdom declared a national incident over a growing outbreak that threatens to spread throughout the country. There have been several hundred confirmed and probable cases so far, mainly in children, and officials are urging caregivers to get their kids caught up on vaccines.

“Given how much measles we’re seeing elsewhere in the world, I expect we will see repeated introductions of measles from travellers,” said Laura Sauvé, past chair of the Canadian Paediatric Society’s Infectious Diseases and Immunization Committee. “I think it’s quite urgent to get kids vaccinated against all vaccine-preventable diseases, including measles.”

Measles is highly contagious and will infect almost every unvaccinated person who comes in contact with it. The virus, which is characterized by a rash and fever among other symptoms, can lead to serious complications, including pneumonia and respiratory failure. About one in 1,000 people infected will develop encephalitis, or brain inflammation, according to the Public Health Agency of Canada. One to three out of every 1,000 people with measles will die as a result of the disease.

Infants under age one face the highest risk of complications and aren’t eligible to receive their first dose until they reach 12 months of age.

“Measles always has to be on everyone’s radar,” said Upton Allen, head of the infectious diseases division at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children.

There have been clusters of measles cases around the world in recent years, including small outbreaks before the pandemic. In Europe, “the rise in cases has accelerated in recent months, and this trend is expected to continue if urgent measures are not taken across the region to prevent further spread,” the December WHO statement said.

Although measles is no longer endemic in Canada, meaning it doesn’t regularly spread in communities and cases are typically brought in by international travellers, a significant swath of the pediatric population is at risk because of low vaccination rates. Ideally, 95 per cent of the population needs to be vaccinated to keep measles at bay. But during the pandemic, because of disruptions to routine vaccination programs, challenges obtaining health care services and increasing vaccine hesitancy in general, coverage rates decreased across the country. While Canada has no national vaccine registry, limited information released by some provinces suggests vaccination coverage against measles and other preventable diseases has dropped by at least several percentage points.

Adults with immune-compromising conditions are also at risk for measles complications. People born before 1970 likely had measles and are presumed immune. Canadians born during or after 1970 should have received one dose of vaccine. It’s often hard to determine vaccination status in adulthood, but people who may be at risk, which also includes those travelling to areas with measles spread, could ask a health professional for an additional dose, Dr. Sauvé said.

“Our coverage hasn’t increased adequately globally” said Shelly Bolotin, director of the Centre for Vaccine Preventable Diseases at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health. “Although we’re doing our best to increase coverage in Canada, we’re not there yet.”

She noted that the country is in a better situation than the United Kingdom, however, which has struggled to contain measles over the years as the disease continues to spread there.

It’s often difficult to know what vaccination coverage is like in Canada because few jurisdictions release updated information on coverage rates, meaning it can be hard to identify immunization gaps.

Shannon MacDonald, an associate professor in the faculty of nursing at the University of Alberta who studies vaccine uptake, said even small dips in immunization coverage could have serious consequences for the spread of vaccine-preventable diseases.

Because of the pandemic, “you’ve got a three-year cohort of kids where coverage is lower, and that’s where you’re at risk of an outbreak,” she said.

Alberta is one of the few provinces that posts recent pediatric immunization coverage rates online, providing a sense of how the pandemic affected vaccination status. In 2022, 82 per cent of children had received one dose of the measles, mumps and rubella vaccine by the age of two, down from 87 per cent in 2019. But there are significant regional variations, meaning some communities face greater risks of experiencing outbreaks, Dr. MacDonald said. For instance, while the 2022 coverage rate in Calgary was 87 per cent, it was only 70 per cent in the province’s southern region.

“When you look at population coverage at a provincial level, it’s hiding these pockets of coverage at an even lower level,” Dr. MacDonald said. “All it takes is one case.”