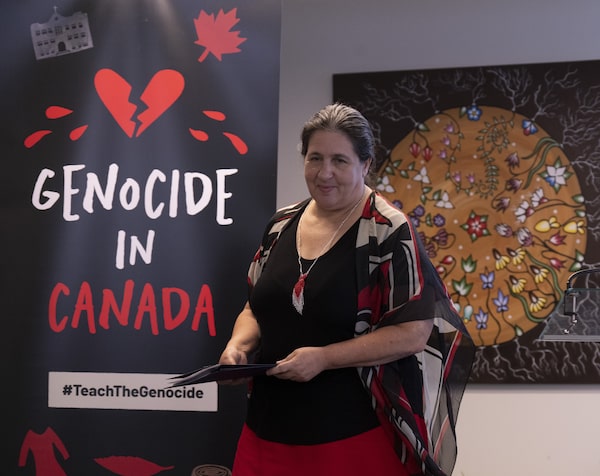

In recent months, two presidents of regional groups in Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island resigned from the Native Women’s Association of Canada’s board, citing complaints around transparency, a toxic work environment and the treatment of former CEO Lynne Groulx, who resigned in April.Adrian Wyld/The Canadian Press

Three regional groups have been expelled from a national Indigenous women’s organization after infighting and allegations of impropriety, which threaten to overshadow this weekend’s annual general meeting.

The Native Women’s Association of Canada, a non-profit organization that receives millions in federal funding, has been embroiled in turmoil since the departure of its long-time chief executive officer last spring, according to letters from former board members and a prominent elder obtained by The Globe and Mail. The former board members describe the current situation as “chaos.”

NWAC is a high-profile Indigenous group that advocates for the rights of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis women and girls, and is marking its 50th anniversary this year. Its AGM begins Friday in Gatineau, Que., where attendees will elect a successor to president Carol McBride, who recently left NWAC, citing health issues.

In recent months, two presidents of regional groups in Newfoundland and Prince Edward Island resigned from the national organization’s board, citing complaints around transparency, a toxic work environment and the treatment of former CEO Lynne Groulx, who resigned in April.

In response to the resignations, NWAC last Friday expelled the local groups from the national organization, along with a third association in Saskatchewan that had supported them.

NWAC said in a statement Thursday that it is working to “restabilize the organization” after a year of sudden changes and suggested that the regional groups were expelled in response to “serious breaches of their fiduciary duties.” The statement says the organization has followed its bylaws.

In letters last Friday defending the expulsion decisions, Ms. McBride also cited “fiduciary breaches” and said the regional groups are “no longer acting in the best interest of NWAC.”

The groups, however, say their immediate removal and ban from this weekend’s general meeting is a violation of NWAC’s bylaws, which give provincial and territorial associations 20 days to respond. They also say Ms. McBride’s resignation also means her successor might be elected at this weekend’s AGM, and the three groups will have no vote on her replacement.

Matilda Ramjattan, president of Aboriginal Women’s Association of PEI, said in a letter that NWAC cannot remove her organization as a member without an opportunity to defend itself.

“That means the [assembly] will be invalid and improper,” she wrote.

NWAC’s statement defended the organization’s decision to expel the regional groups and said it acted in the best interests of the association.

“A lot of difficult decisions have been made, most of which came from the need to restore financial accountability and transparency, and to recover from decisions involving millions of dollars that were spent without full board knowledge or approval,” the statement says.

In letters to Ms. McBride and NWAC’s board, the local presidents also raise complaints about interim CEO Madeleine Redfern, who they say moved her family into the organization’s resiliency lodge in Quebec, which is intended for community use.

Lorraine Whitman, a past president of NWAC, specified that the lodge is meant for women, girls and gender-diverse women to have a safe space to heal.

“That’s not acceptable to me, and I need to speak out,” she said in an interview.

NWAC declined to comment on Ms. Redfern’s living situation but said the lodge had been unoccupied and is in disrepair, which meant it could not be used for programming for Indigenous women.

In an interview, Ms. McBride said she couldn’t discuss why the regional groups were removed because there could be legal ramifications.

She defended the work of the organization and said it is being restructured to support women and their families.

“We felt that it was to our advantage to have our interim CEO live there and to be able to keep an eye on what was going on there,” Ms. McBride said about Ms. Redfern living in the resiliency lodge.

She denied the organization is in chaos, as “we have come a long way since April and we have found out a lot of things, and the board has taken the right decisions.”

She said she chose to leave the organization after seven years because she is tired and suffering from health issues: “Since joining NWAC as president, I’ve been through hell and back right from the get go to now, and now my health has taken its toll.”

Alma Brooks, an 81-year-old elder who worked with NWAC for more than four years, also resigned from her position as a member on the board. She said in an interview that she was told earlier this year that the plans for a second resiliency lodge in New Brunswick, which she helped spearhead, was being shut down because of lack of funds, despite having secured private contributions.

The organization also underwent a federal audit in recent years. Ms. Groulx, the former CEO, said under her tenure the organization had a “robust” system to control finances, with no major issues.

She said she couldn’t discuss the current situation at the organization but said bylaws must be carefully followed.

“Lawsuits could certainly ensue and elections could be reversed,” she said.