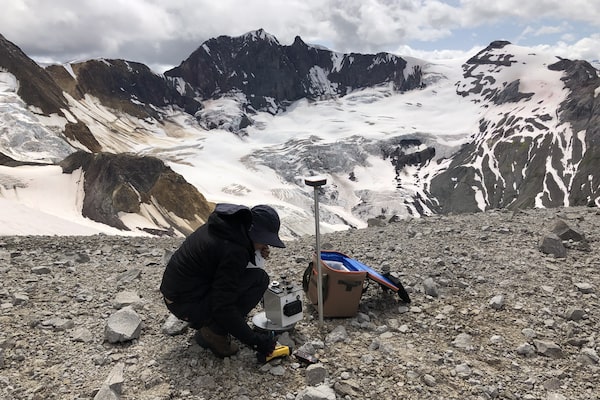

A team of scientists are planning a 'CAT scan' of a British Columbia volcano to help harness the underground heat that turns rock into magma for renewable energy.HO/The Canadian Press

Scientists are planning a “CAT scan” of a British Columbia volcano to help harness the underground heat that turns rock into magma for renewable energy.

“Canadians are often surprised to know there’s volcanoes in the country,” said Steve Grasby, a geologist with Natural Resources Canada. “But there are active volcanoes.”

Mr. Grasby and his colleagues are headed about 24 kilometres west of Whistler, B.C., to Mount Cayley, part of the same mountain chain as well-known volcanic peaks such Mount St. Helens in Washington State.

Cayley’s last lava flow was back in the 1700s, but plenty of heat remains. At nearby Mount Meager, a well drilled in the 1970s showed temperatures of 250 C at 1.5 kilometres depth.

That much heat at such a relatively shallow depth is a great opportunity for geothermal energy, Mr. Grasby said. For comparison, underground temperatures in Alberta – where some see geothermal potential in the energy wells dotting the province – only rise by 50 C for every kilometre of depth.

“In terms of temperature, it’s a world-class resource,” Mr. Grasby said.

But how do you tap it?

Geothermal plants generate power through the heat contained in underground water. Their success depends on sinking wells in just the right place to find the most water at the highest temperatures.

Mr. Grasby said because the work is so expensive, geothermal drillers need a 50-per-cent success rate to be viable. Oil and gas drillers, he said, only need to be right one time out of seven.

He and his colleagues are trying to find ways to help drillers improve their hit rate by building a 3-D map of Cayley’s innards – without using traditional tools such as seismic lines.

Part of the map will be drawn through basic geology. The team will analyze which rock types are present to find out how permeable or porous they are, or locating and diagramming fault systems that may hold hot water.

But they will also use methods such as examining how electromagnetic energy moves through the volcano. For example, when lightning strikes – even in a remote part of the world – the geologists can examine how that energy moves through the earth, where it is being absorbed and where it passes through.

“We have to go all around the volcano, so you’re looking into it from all these different angles,” Mr. Grasby said.

“You can start to develop a 3-D image of what’s underground. By collecting these observations all around the volcano, you can start to see there’s a magma chamber at 10 kilometres depth or a hot fluid-filled reservoir at two kilometres.

“You can think of it as a CAT scan.”

That alpine scan could be used by drillers to determine exactly where to position themselves to get to the best heat resources.

“Our goal is to reduce that exploration risk,” Mr. Grasby said. “You can’t afford to drill a lot of dry holes.”

Canada has a few geothermal projects under way.

Companies in Saskatchewan and B.C. have drilled wells and a couple more have plans. Alberta has recently joined B.C. in developing a regulatory regime for geothermal development.

But no geothermal wells are yet producing energy, making Canada the only country in the Pacific Rim of Fire not to do so.

The energy source could be a significant zero-carbon contributor to Canada’s energy needs, Mr. Grasby said.

“Until someone sees a producing geothermal well, it’s hard to believe it could be true. You need to see that first one,” he said.

“It’s not going to be the saving grace, but geothermal could be a big contributor, that’s for sure.”

We have a weekly Western Canada newsletter written by our B.C. and Alberta bureau chiefs, providing a comprehensive package of the news you need to know about the region and its place in the issues facing Canada. Sign up today.