For runners, the definition of folly is repeating exactly the same motion 10,000 times an hour and expecting not to get injured.

That's the thinking behind standard advice to vary the terrain you run on, alternate between different pairs of shoes and mix different forms of cross-training into your routine. The more you mix it up, the less likely any given body part will break down.

But as high-tech gait analysis systems reveal increasingly subtle details about how we run, a more complicated picture is emerging. For some injured runners, too much stride-to-stride variability may be the problem. They may have muscle weaknesses or imbalances that allow their hips, knees and ankles to wobble in slightly different directions with each stride – and the solution is rehab exercises that produce a more consistent stride.

In this case, the goal is "a more predictable movement pattern," explains Dr. Reed Ferber, a top biomechanics researcher and head of the University of Calgary's Running Injury Clinic. "The body knows what to expect for the upcoming footfall, and the muscles can adjust accordingly."

Ferber's research relies on a sophisticated 3-D gait analysis system that uses multiple video cameras to capture and analyze every detail of a subject's running motion. The system is now deployed at more than two-dozen labs and clinics around the world (for a list, see runninginjuryclinic.com), and Ferber has a database of thousands of runners to compare results with.

He initially expected that the database would reveal simple relationships between stride abnormalities and running injuries – knee pain might result from too much hip rotation, for example. But no matter how much data he collected, these links remained elusive.

Instead, the biggest difference he noted was that, in healthy runners, the data from each stride looked almost exactly like the data from the previous stride. In injured runners, on the other hand, the joint angles and motions were slightly different with each stride, though these variations were invisible to the naked eye.

This suggests that you can't diagnose running problems simply by watching someone run. Ferber recalls a patient who had a distinctly knock-kneed gait – "you could see her coming from miles away along the running paths" – and was perennially injured despite having spent years trying to correct this problem. Ferber's analysis showed that her stride was also highly variable; a program of hip-strengthening exercises gave her a more consistent stride and cleared up her injury problems, even though the knock-kneed stride persisted.

While the evidence so far is suggestive, more research will be required to determine whether stride variability might be as much a consequence as a cause of injury. That, too, would explain why injured runners display greater variability that diminishes once they get healthy again.

"Good treatment that addresses the pain may end up changing the variability," notes Greg Lehman, a physiotherapist and chiropractor who oversees the use of one of Ferber's 3-D gait analysis systems at Toronto's Medcan Clinic.

In addition to the gait analysis, Lehman gives patients a series of running-related functional tests such as one-legged squats, to look for physical characteristics that might affect their running. Even without 3-D motion analysis, these simple tests can help therapists identify potential problem areas.

"If I can identify a limitation in basic function, like ankle dorsiflexion, it might help me understand why someone runs a certain way," he says. "On the other hand, if they have something structural like bowleggedness, then I know I can't correct this and shouldn't try."

Variability isn't all bad, both Ferber and Lehman stress. In healthy runners, mixing up different running routes, surfaces, paces, shoes and so on is a great way to apply "daily positive stress" that strengthens the very muscles needed to maintain a consistent stride, Ferber says.

But injured runners have different needs.

"During rehab, we ask our patients to limit variability," he says. "Stick to one route, on one surface, with one set of shoes, and so on. Once they're injury-free, the focus can shift back to training and varying the program."

Alex Hutchinson blogs about exercise research at sweatscience.runnersworld.com.

How's your running form?

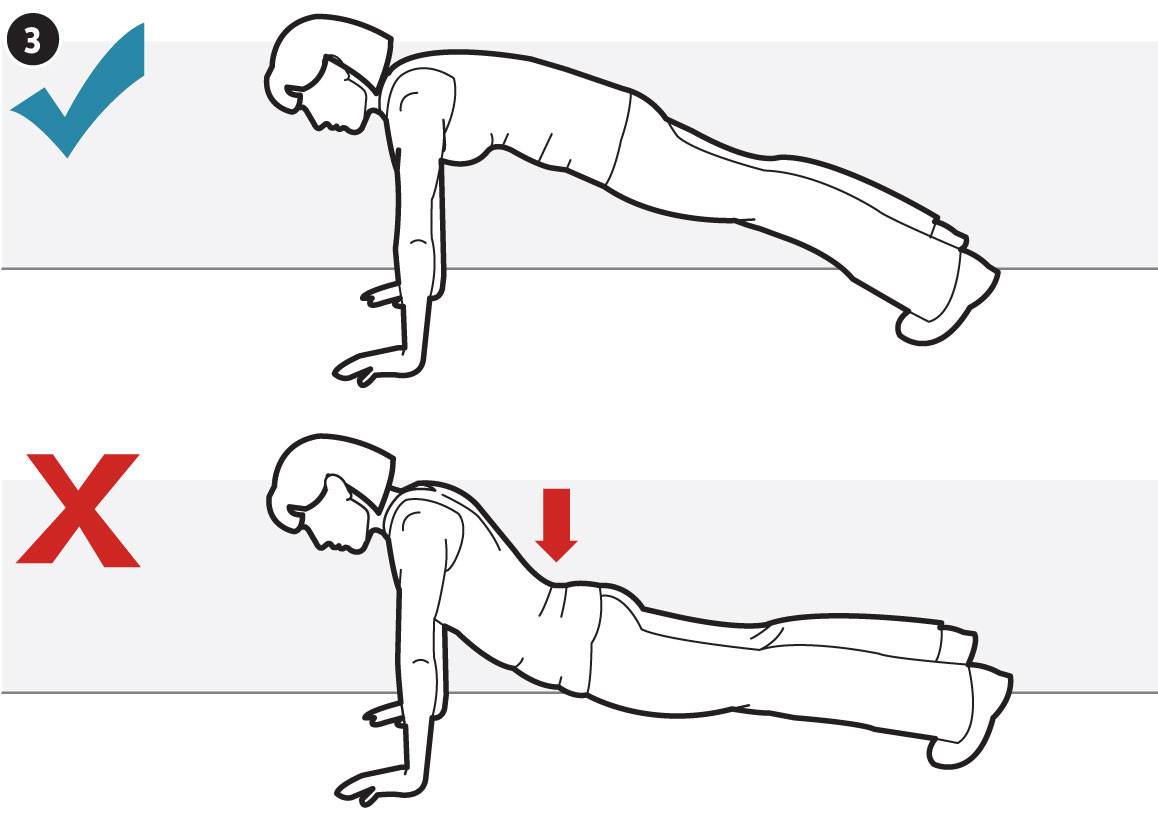

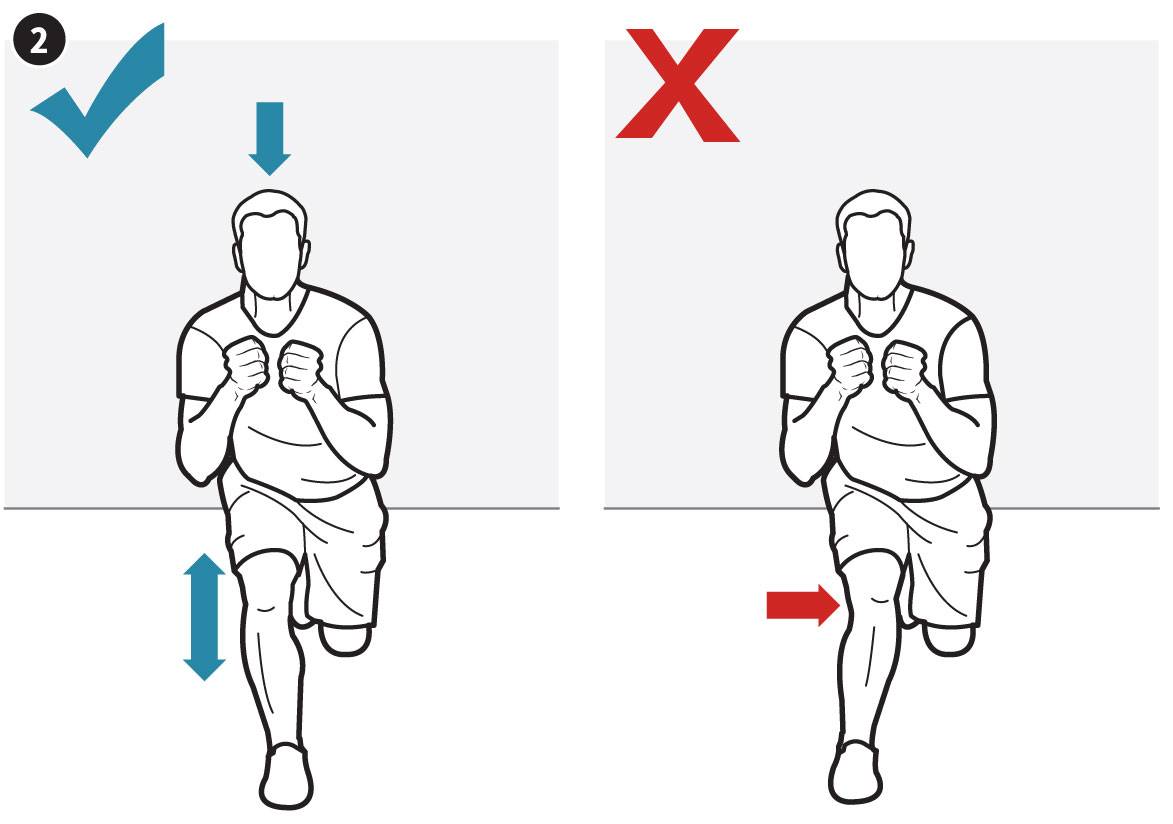

Try the following three tests, recommended by Toronto chiropractor and physiotherapist Greg Lehman, to check for functional limitations that may be affecting your running stride.

Ankle dorsiflexion

Single-leg squat