Ahmed Maher, 83, stands outside his home in the Majid house, built in 1880, which he hopes will not be demolished, across The City of the Dead, where a new construction project is underway on the Salah Salem road in the capital city of Cairo, Egypt, on May 25, 2023.HADEER MAHMOUD/Reuters

The City of the Dead, to my surprise, was full of life.

Like many foreigners, I had avoided this vast necropolis during my visits to Cairo, choosing instead the classic haunts – the Pyramids, the Egyptian Museum, various popular mosques. The name alone sounded foreboding. Some locals, or Cairenes, I talked to described it as a vast dusty slum, implying it was a no-go zone for guileless visitors.

Instead, I found the area fascinating and intriguing – a delight overall. But it also filled me with fear – fear that Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi will eradicate vast portions of the City of the Dead, as he seems intent on doing.

Read also: Death - and plenty of life — on a Nile River cruise

Thousands of tombs are being bulldozed to make way for roads and bridges as part of el-Sisi’s construction campaign. Already, the southern part of the City is dominated by a new, elevated roadway, the Bridge of Civilization leading to the New Administrative Capital – Egypt’s government quarter, which is rising from the desert about 40 kilometres east of Cairo.

One of the towering minarets of the Khanqah of Faraj ibn Barquq funerary complex, with author Eric Reguly peering over edge on the rectangular balcony.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

I visited the City on a warm day in early April with a local guide who believed that living among the dead, an old pharaonic idea, was nothing unusual in Egypt.

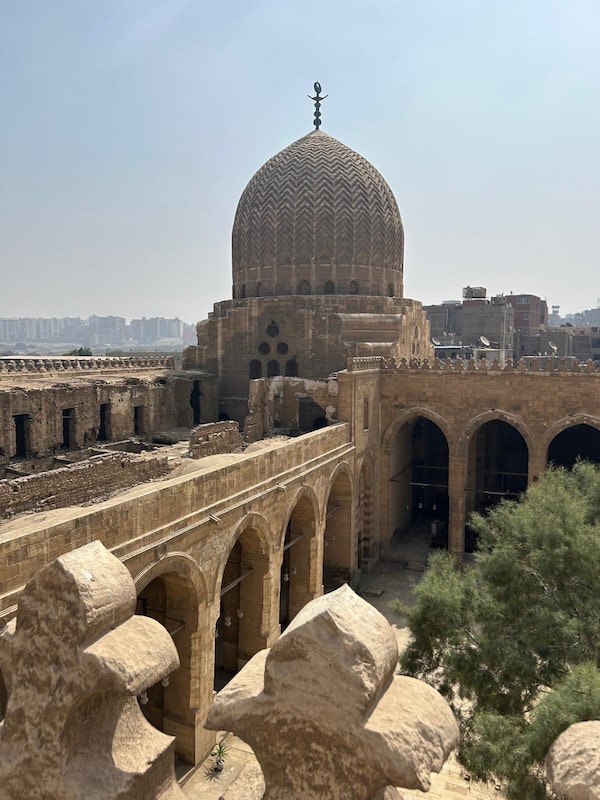

We began the tour at the Khanqah of Faraj ibn Barquq, the religious funerary complex built by the Mamluk Sultan Faraj in the early 1400s. The Mamluks were originally non-Arab slave soldiers and freed soldiers who came from what is now Turkey and the Russian Caucasus. Their sultanate ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz (the west coast of Saudi Arabia) from the 13th to the 16th Century, when they were conquered by the Ottomans. Today, the northern portion of the City is full of Mamluk tombs, of which the Khanqah is the most impressive.

It was built around a vast courtyard and had residential quarters, schools and a mosque, which is still active. The male and female mausoleums are covered by soaring ornate domes, which, at more than 14 metres across, are the biggest of their kind from the Mamluk era. Saeed, one of the Egyptian guardians of the Khanqah, took us inside the male mausoleum, cupped his hands to his mouth and, with his deep, powerful voice, sang a prayer. I felt myself tingling as his voice reverberated through the void.

Another view of the Khanqah of Faraj ibn Barquq funerary complex in the City of the Dead.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

He then took us to the roof of the Khanqah, after which we climbed the narrow corkscrew stairways of one of the twin minarets. The views were worth the skyward hike. They showed the sheer vastness of the City of the Dead, which stretches for six km – four km across at its widest point – and forms part of historic Cairo, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

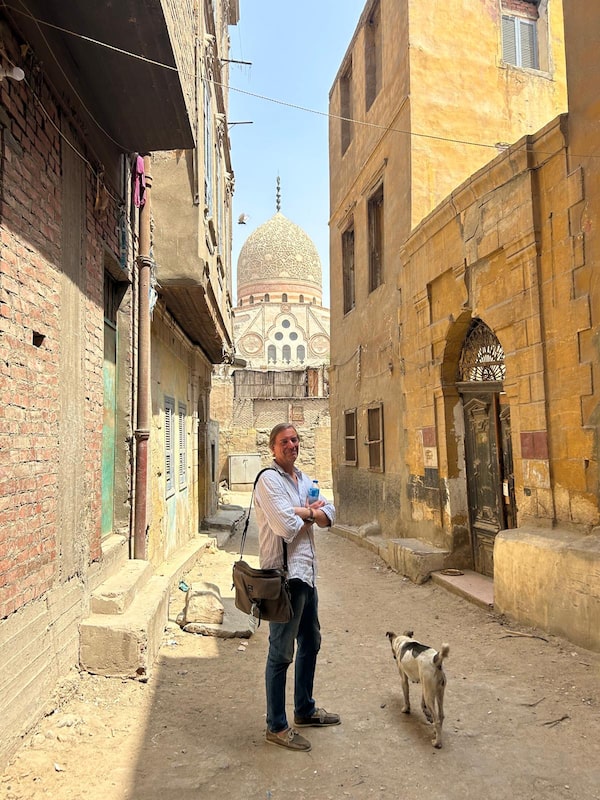

When we stepped down to Earth, my guide and I strolled through the City. The area was full of artisans, workshops, bakeries, grills, tea spots and convenience stores – all of them charmingly dilapidated and cluttered but perfectly functional. People lived among the tombs and mausoleums, some in shoddy brick apartment blocks that were erected without permits in recent decades. In one overgrown alleyway, we spotted an ancient limestone bathtub next to the carcass of what looked like a 1920s’ Model-T Ford.

We ended the tour with a visit to the Sultan Qaytbay Mosque, a Mamluk gem built in the 15th century. It was richly decorated, with magnificent stained-glass windows and an ornate water trough for horses and camels just beyond the main structural walls. In both the Qaytbay and the Khanqah, we were the only tourists. It was bliss – no diesel-belching tour buses, no souvenir shops full of Chinese-made tat, no overpriced coffee shops.

Saeed, one of the guardians of the Khanqah of Faraj ibn Barquq in the City of the Dead, sings a prayer in the male mausoleum of the funerary complex to demonstrate the reverberation effect of the soaring dome.

Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

No one knows how many people live in the City; estimates range from several hundred thousand to a million or more, with the northern section of the necropolis more livable than the southern one. But big expanses of the City are at risk and many archaeologists, architects, historians and city planners inside and beyond Egypt are alarmed by what the government has in mind for the area as it “modernizes” Cairo.

Basem Kamel, secretary-general of the Egyptian parliament’s small Social Democratic Party, suspects the City of the Dead faces the wrecking ball, at least parts of it. “The mentality here is to build roads and bridges,” he said. “This will hurt our history.”

Since el-Sisi came to power in 2014, new infrastructure to move cars, buses and trains has been his main development pursuit. Egypt’s population has more than tripled since the 1970s and new cities are sprouting in the desert, one of them being the New Administrative Capital. Official figures show that 7,000 km of roads and some 900 bridges and tunnels have been built everywhere. The urban development projects have cost US$500-billion.

The author, Eric Reguly, on a narrow street in the City of the Dead, with the dome of the Sultan Qaytbay mosque in the distance.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

Already, a six-lane road bisects the northern and southern parts of the City and the foundations of the Civilization Bridge have cut into stretches of the southern part. Tombs are being torn down, even those of some of the famous. In February, the remains of Queen Farida, the first wife of King Farouk, who ruled Egypt from 1936 to 1952, were dug up and transferred to another cemetery (Farida lived in what is now the official residence of the Canadian ambassador from 1948 to 1951).

Last August, Omniya Abdel Barr, an architect whose specialty is cultural conservation, appealed for help as the demolitions continued. “Help! Inhumane creatures are destroying our heritage,” she said on X. The same month, several members of a government-appointed committee tasked with documenting heritage buildings of outstanding historical significance resigned in protest of the destruction of mausoleums.

International petitions signed by architects and urban planners pleading for the mausoleums’ preservation circulated. Amro Ali, a former professor of sociology at the American University of Cairo, used X to note, “The level of blindsided greed, self-entitlement, and impunity it must take to destroy your own beautiful heritage when even foreign wars and colonial endeavours didn’t dare touch it.”

The government has defended its modernization program as a way of eradicating slum areas. It also insists that antiquities in historic Cairo will not be touched, though conservationists have said that the protection system is haphazard. They note that some precious buildings are not registered as antiquities.

The interior of the richly decorated and serene Sultan Qaytbay mosque, a Mamluk-era gem built in the 15th Century.Eric Reguly/The Globe and Mail

It appears that much, maybe most, of the City of the Dead will survive, though the more popular parts could see their fairly modern apartment blocks torn down, and their residents relocated to new suburban towers. Doing so might leave the City more or less intact but lifeless as their residents are ejected.

If you go

Visiting the City of the Dead is best done with a local guide, not because it is unsafe – it is not, though beware petty crime – but because you will get lost in the maze of streets as you try to find the area’s highlights. One popular travel company is Travco, travco.com. Another is Memphis Tours memphistours.com.

If you go on your own, stick to the northern side of the City, where the main mausoleums and mosques are located. There are no entrance fees to the main sites, but handing the equivalent of a few dollars to whoever lets you in is polite.

Female visitors are welcome to visit mosques and mausoleums but are expected to cover up. Bare arms and short skirts are considered disrespectful. A simple head scarf should be worn.