Watch the video to meet the students, principal and support workers who are determined to make Dennis Franklin Cromarty High School a success

In the girls’ washroom on the first floor of Dennis Franklin Cromarty High School, the lighting is harsh. There’s a communal sink for handwashing and a row of aging toilets. In the stall at the end of that row, the door doesn’t quite fit the frame. In other words, it’s like high-school girls’ washrooms everywhere – right down to the graffiti on the wall of that final stall. But rather than calling someone a slut or spelling out random vulgarities, this bit of scrawl asks a simple (if exuberantly punctuated) question: Do you know your potential?!

Getting students to answer that question in the affirmative is what DFC High is all about. The school is one of two (the other is almost 400 kilometres away in Sioux Lookout) run by the Northern Nishnawbe Education Council, a First Nations nonprofit organization established by the bands of more than 20 fly-in reserves in Ontario’s northwest.

The organization’s “vision statement” aims to help bring into being “a world in which First Nations people succeed without the loss of their identity, and have the courage to change their world according to their values.”

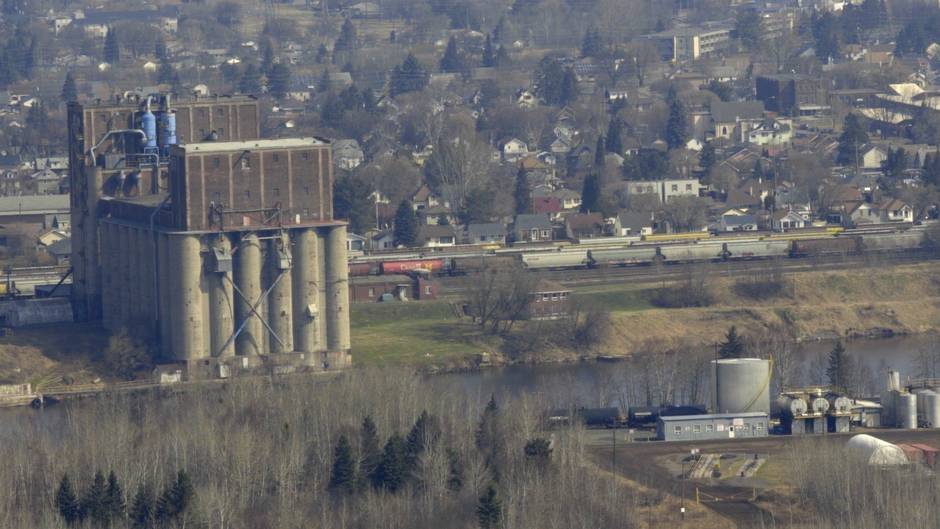

DFC students come from those same reserves – some of the most isolated communities in Canada. The school sets them up in Thunder Bay boarding homes, assigns them a “prime worker” (equal parts guidance counsellor, social worker and parental figure), and enrolls them in courses approved by the Ministry of Education.

It also strives to have graduates leave not only with a diploma but the skills, knowledge and confidence to help their home communities heal – by setting positive examples, showing a pride in indigenous culture and identity, and fostering employment on reserves.

About 2,000 students have walked its halls in DFC’s 15 years of existence. They come from families that have survived the destructive legacy of the residential school system, but DFC is a residential school in name only. It is funded by the federal Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development, but its direction and administration are run by aboriginals, and the students leave home to attend this high school by choice, and with their families’ permission.

“Most of us, as parents, would not choose to have their kids up and moved from their community and home at the age of Grade 9,” says Sonia Prevost-Derbecker, vice-president of education for Indspire, an indigenous-led charity based in Toronto. She realizes that boarding schools present a challenge to remote communities but, in some cases, sending children away to school is their parents’ only option.

“The experience can be most isolating and terrifying and, without some sense of belonging, kids fall through the cracks all of the time,” she says. “It’s a risky time in a kid’s life to be doing that.”

Unfortunately, many of the grandparents of the students at DFC are all too aware of this, as they are survivors of a residential school system that saw more than 150,000 youngsters torn from their homes. For the century it was in existence, it employed shame, violence and deprivation to teach indigenous children that their traditional way of life was not only wrong, but evil.

That abuse, disguised as legitimate education, led to the loss of countless cultural traditions and many indigenous languages. It also left a legacy of broken families. Students were robbed of the experience of growing up in a loving home; then when they had children, they often didn’t know how to be parents. It is a pattern, survivors say, that continues to repeat itself.

“How do you learn in an environment of trauma, fear and shaming?” asks Marie Wilson, a member of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRC), which released its momentous final report on the legacy of the system this month.

Ms. Wilson sees in experimental initiatives like DFC the potential to help to heal the lasting trauma. As well, the new schools can play a role in erasing the stigma around education for many indigenous people who still distrust the system.

DFC has had its share of tragedy, and is by no means a perfect solution – but Ms. Wilson says any experience that “helps to put students’ minds to learning as opposed to protecting themselves and surviving,” is a great opening, adding that schools like DFC “definitely have to be better than the historic alternative and [should] be appreciated in being bold and therefore important.”

Principal Jonathan Kakegamic also believes his school can help with the healing, and says the key to that process is rebuilding a connection between culture and identity because, without it, students can’t be successful.

“For residential schools to say, ‘You’re no good, you can’t speak your language’ – that does something to your identity, to your psyche,” he adds.

Mr. Kakegamic is originally from Keewaywin First Nation northwest of Thunder Bay near the Manitoba border, but grew up in the city. Although his parents went to residential school, they didn’t tell him about their experiences until he was in his 30s. Hearing their stories of survival helped him to solidify his identity. And he hopes that fostering a positive learning experience for the kids at DFC will have a similar effect.

“They know who they are when they leave here. … They need to know they are First Nations, that you can be proud of who you are.”

Appearances and assumptions

DFC is housed in a former vocational school that, from the street, doesn’t look much different from nearby Sir Winston Churchill Collegiate. But around back is the first clue that this is a unique place. There is an open tepee and fire pit, where Bella Patayash, the in-house elder responsible for teaching traditional skills, sometimes cooks.

When the bell rings in the morning, students funnel in after cascading off public buses. They shuffle-walk down the halls, and file neatly into their classrooms. With only 150 kids (ages 14 to 21) in the entire school, the classes are smaller than normal, maxing out around 20. That allows for more bonding between teachers and students.

DFC follows a curriculum the province sets out and has a full roster of teachers for all the standard topics: English, math, business, gym, science and shop. In addition, students study indigenous language and spend their spares in the Elders’ Room, where they sip Red Rose tea and practice traditional activities, such as beading and bannock-making.

In so many ways, however, it is just like every other high school – kids hang out in the hallways during lunch, goofing off and giggling; they populate the gym after school, practicing basketball. If one thing sets the atmosphere apart, it’s the quiet, calm vibe that permeates the building. The students are soft-spoken and more polite than most teens – opening doors for teachers, patiently waiting in line for lunch, and paying attention during school assemblies.

“When the school first started, the Thunder Bay police wanted to put an office in here – a gang office,” says Mr. Kakegamic. “They thought they knew us. They had assumptions of how it was going to be.”

But the school has not been without its troubles.

Since it opened, seven students have died while enrolled, in many cases found in one of the rivers that run through the city. Students and staff believe these deaths were accidental – the victims were probably intoxicated and fell in. But one graduate was found hanging from a tree in a public park with a noose made of Christmas lights around his neck. In 2011, the province’s chief coroner heeded indigenous leaders and called a joint inquest into the deaths, with hearings to begin this fall.

Two years earlier, the situation was so grim there was talk of closing the school. Instead its leadership was changed – Mr. Kakegamic was put in charge – and new support teams were developed to help the students deal with some of the challenges they face: loneliness, addiction issues and depression.

“For students who are away, it doesn’t change one element of the residential-school period, which is that emotional distance between the student who is away and the parents left behind,” says Ms. Wilson. “The issue of homesickness is still a factor.”

Daniel Levac wasn’t homesick.

“He was one of the students I never had to worry about, whether he was in class or at home at night,” says his prime worker, Lyle Fox. “He was the kind of guy who would ask how your day was – but he wasn’t just asking, he would sit and listen. And he did that to everybody. It wasn’t just me or just his friends. It was the quiet student in the corner, too.”

But Daniel’s time at DFC ended abruptly last fall, when he was fatally stabbed on the steps of the SilverCity cinema. A young man also from a remote northern reserve has been charged with second-degree murder.

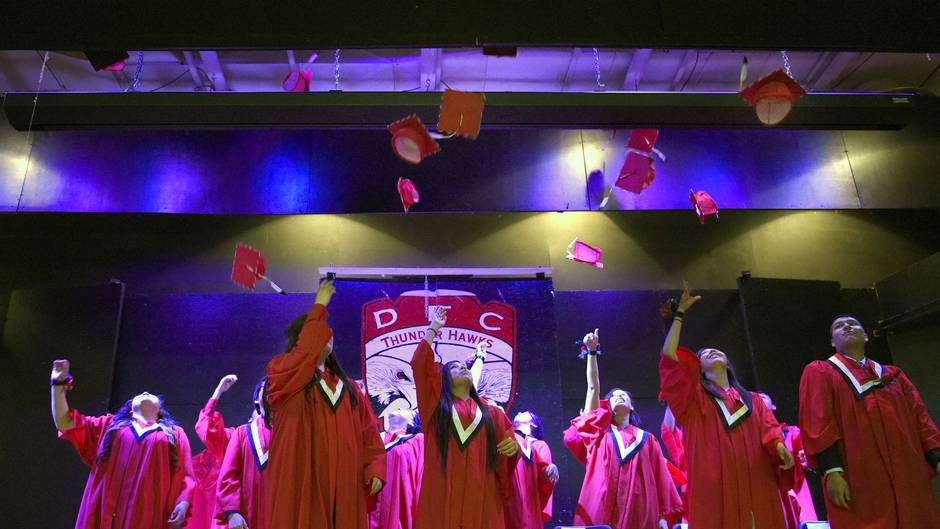

Mr. Levac, 20, was set to graduate this year. In his honour at last month’s ceremony, the school had a memorial cap and gown placed on a chair alongside the other grads as his parents watched from the audience.

The cap and gown were brought on stage by his grieving prime worker. “It took a lot out of me because I have a lot of guilt that comes with it,” says Mr. Fox, 32.

He realizes he couldn’t have stopped what happened. “But I was responsible for him; he was in our care.”

Breaking the cycle

Juliet Aysanabee’s favourite saying is “Just kidding.” In fact, she says it after pretty much every sentence, whether she means it or not. It’s almost like a special teenage punctuation – part goofy, part shy, part playful.

She is tall and thin, mostly limbs. Her long brown hair is pin-straight and generally hangs over her glasses. She likes to wear leggings and hoodies, and she carries headphones wherever she goes. When she arrived, she was shy, but has opened up, and especially enjoys drama and gym classes. After school, she hangs out with her friends at the mall; in the evenings, she plays sports.

Like some of her classmates, Ms. Aysanabee, 18, came to DFC after spending most of her youth in foster care. She cannot pinpoint exactly when she left home in Sandy Lake First Nation (across the water from Keewaywin, about 600 kilometres northwest of Thunder Bay) and her six siblings, but knows she spent eight or nine years being bounced from foster family to foster family, sometimes spending as little as a month in one home. “For as long as I can remember, I was always moving around,” she says. “But here I am.” She is embarrassed by this part of her history. “When my friends talk about what their moms did when they were younger,” she says, “I don’t really have anything to talk about.”

Ms. Aysanabee wasn’t reunited with her mother until she was in Grade 8. And then, just two years later, she was off again. But this time, things were different. This time, the move was her own choice, part of a bigger decision she had made: to get her high-school diploma.

Since arriving, she has integrated herself into the school’s family. She has participated in plays, joined the broomball team, made friends. She even got a job with the foot patrol, a group of current and former students hired to walk the downtown core and riverbanks Thursday, Friday and Saturday night during the fall and spring terms – on the lookout for classmates up to no good.

“We’re walking around and telling on people who are drinking. Being a rat – a snitch,” she says with a giggle. “I just hope I don’t bump into any of my friends.”

Prime worker Lyle Fox’s sister Clarissa is part of another team, one made up of adults who patrol the city in minivans all night responding to student emergencies. She, too, is motivated by personal experience. “My father has shared his stories with me,” says Ms. Fox, 39, referring to the “mental, emotional, physical, sexual and spiritual” abuse he says he endured while at Shingwauk, a residential school in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont. “He was basically broken down.”

After growing up, “my father didn’t know how to be a parent ... how to love people. So when he and my mom got together, all they did was drink and fight. I think a lot of families were like that.”

By understanding this legacy, Ms. Fox is able to relate to the students who come to DFC. She knows what it is like to be stuck in the destructive cycle from the residential school system. She knows what it is like to have a broken family and loved ones who struggle with addiction. But she also knows that people can be healed, as her father has. And as a result of his strength and his story, she and most of her siblings don’t drink.

“We are breaking that cycle,” she says.

Finding roles within the school

Mr. Fox also understands the importance of breaking that cycle and reclaiming his indigenous identity. He says that learning about a traditional way of life saved his life when it was spiralling out of control.

Now he is working to bring cultural teachings to the school that go beyond the current program, through which an in-house elder teaches students such traditions as beadwork and bannock.

But at 21, he had been an addict for nine years. Using drugs (such as cocaine and Percocet) and alcohol, he says, “filled a gap in my self-esteem. It made me feel good, made me feel better about myself. It gave me courage so I didn’t have to walk home at night feeling scared.”

Mr. Fox hit bottom after three suicide attempts that followed his 19th birthday – the day his older brother, Darryl, died of lymphomatic cancer. But his life turned around at the Benbowopka Treatment Centre in Blind River, Ont., a facility that combines traditional indigenous health practices with Western medicine.

“That’s where I was introduced to the traditional side of me. I started to learn about my culture, my identity and the spiritual side of our life,” he says. “My culture saved me. My teachings saved me.” Now sober and a father of four, Mr. Fox is being initiated into the Midewiwin, a society that practises traditional medicine and healing through ceremony.

For him, part of the antidote to the poison that was the residential-school system is providing students with opportunities to discover their heritage of harmony, respect and spirituality; his efforts at DFC have prefigured part of what the TRC has asked for in its report. The 64th of its 94 recommendations calls on all levels of government to work to provide indigenous students with instruction in traditional spiritual beliefs and practices.

This past school year, Mr. Fox built a grandfather drum (big enough to be played by several people) with the help of students, many from reserves where traditional lifestyles are neither common nor celebrated. Next year, he hopes to hold after-school sessions so students can learn to make and play smaller drums of their own.

But he has a lot of convincing to do. “In our area in the North, a lot of young people are following the footsteps of their parents and grandparents – the residential school system told them that our ways are evil,” he says.

In fact, the first time he held a drumming session, only four or five students came by and, the next time, there was just one. “I think that whole mentality is still lingering.”

Downright Dirty

The lingering is hardly limited to indigenous people. The residential schools were built on racism, and created ripples of damage, violence and entrenched prejudice.

“Sometimes, I feel like people judge me cause I’m aboriginal. I don’t like the way they look at me. They look so grossed out or something,” says Ms. Aysanabee. “I was walking on the sidewalk, and some person walked by me and pointed at me and called me a butthead.”

To say she feels alienated from the city at large is an understatement, and perhaps not surprising, considering the existence of something like Thunder Bay Dirty. Comprising several Facebook pages, a Twitter feed and YouTube channel, it is effectively an online forum for shaming indigenous people who are either in desperate situations or appear to be.

Thunder Bay Dirty is full of racist assumptions, one of which had a direct impact on DFC student Frank Kakepetum, a friend of Ms. Aysanabee. He was featured in a photograph that was snapped as he happened to being leaning against a brick wall, his head tilted back, his mouth agape and his eyes closed.

In person, he seems very much like a normal high-school kid – as the spring term wrapped up, he kept busy by building a tikinagan, a traditional bassinet, for his sister’s baby. But the caption for the photo on Thunder Bay Dirty accused indigenous people of being so lazy, they can sleep on their feet. “Ha ha lil Oxy nod,” read one particularly caustic remark.

Mr. Kakegamic realizes that stereotypes die hard. “A citizen of Thunder Bay, a non-native – if he doesn’t know anything about us, he is probably going to be on guard. And he is going to have these presumptions of how Indians are. When you have that assumption, you’re already eliminating any acceptance.”

There are, though, benefits to having DFC located in Thunder Bay, according to Ms. Prevost-Derbecker of Indspire.

“They have the ability to retain teachers and they are in a city with a fairly significant indigenous population, so they have the ability to get some demographic representation in the classroom, which is very important,” she says.

Having indigenous teachers, even if they are from the city and not from the students’ home communities, she adds, can make it easier for the kids to connect, build trust and act as a role model.

But one criticism of the school is that even city residents who want to get to know its students don’t have the opportunity. To one observer, it’s a “reserve bubble” sitting in the midst of the city.

And it’s true, says Mr. Kakegamic, that, when classes are out for the day, many students stay on the property. Rather than, say, participating in local sports leagues, they take part in after-school programs run with the help of the Dilico Anishinabek Family Care group.

When the bell rings at the end of the school day, Dilico workers set up shop in a dedicated room. What they offer is more somewhere to hang out – with TVs, video games, and plenty of popcorn and hot dogs – rather than a set of activities. They also help out with the sports teams and attend school dances.

But in reality, at least part of the reason the school shelters its students so closely is to provide a greater degree of safety. If they go to after-school jobs or an outside community centre for programming, there are many unknowns to take into account.

Measuring success

In 2011, the National Household Survey conducted by Statistics Canada showed the high-school graduation rate among non-aboriginal Canadians sat at about 89 per cent. In 2012, Statistics Canada found that the graduation for off-reserve indigenous people was 72 per cent.

At DFC, though, Mr. Kakegamic doesn’t measure success using percentages, in large part because his students arrive with a broad range of educational backgrounds and progress at a pace that is more fluid than in a regular high school. Instead, he points to the actual number of students that his team has managed to help make it through to graduation. This spring, there were 20 – about the average in recent years, although 2014 reached 29, setting the record.

Graduation rate is only one measure of success, says Ms. Wilson of the TRC.

“There is room at this point in our history for lots of [indigenous education] models. I think this is a time for bold experimentation and patience for things that may or may not be perfect off the top.

“But we do know that doing things the same old way, with the same old structures and the same old people in charge is not leading us to good results.”

And it is true that the school is not perfect yet. Every year, anywhere from 30 to 50 students return home before classes end. Some leave by choice, usually citing homesickness; others, because of their behaviour (usually related to acting recklessly while intoxicated).

Getting to the roots of that behaviour can be a complex task, but according to many who work with DFC students, it can also involve basic building blocks, such as one truly important part of their identity: the Oji-Cree language.

Sarah Johnson teaches it and says that “the federal government’s aim” with the residential schools “was to have the language disappear. But it survived because those students that survived were able to speak the language among themselves under their blankets in their beds.”

Respecting language is one of the key elements of healing pointed to by the TRC, which calls for “protecting the right to aboriginal languages, including the teaching of aboriginal languages as credit courses.”

Ms. Johnson is originally from Weagamow Lake First Nation, and her classroom looks like any language-teaching space.

At the beginning of each term, DFC students are given a worksheet and a speaking activity to assess what they know. “Most come in with very little knowledge,” she says. “There are some who understand what is being said, but they cannot speak it. It seems language is not valued, especially by young parents – and the elders are slowly dying.”

One encounter still bothers her a decade later. She was working at a language centre in Sioux Lookout when a young boy asked: “How come you’re teaching us a foreign language?”

“It was upsetting,” she says, “because that’s who we are.”

For Ms. Johnson, it’s simple: If you erase the language, you erase the culture.

Graduation day

It’s a sunny Wednesday afternoon as this year’s 20 graduates shuffle into a conference room – a space usually off-limits to students – to change into red and black gowns and don feathered and beaded mortarboards. Once everyone has put on the celebratory garb, the photos begin: both official group shots and then a whole lot of selfies.

As the graduates spill out into the hallway – giddy, and a bit nervous – as smiling, teary-eyed staff fuss with the caps and gowns, making them just right.

But with the arrival of summer, there is also a tinge of worry in the air. “We do so much work with them through the year and then they have to go back,” says prime worker Saturn Magashazi. “There’s no continuity through the break.”

Still, for the students, summer promises exciting times – and a chance to be with their families. Ms. Aysanabee is especially pumped to see her mom and her siblings back home. And this summer, she plans to work so she can save for her final year at DFC.

After that, she has big plans. “Sometimes, I think about what I can do when I grow up – I mean, I am grown up – so when I get older,” she says with a smile, sitting on the floor in the hallway, her legs wrapped up under her. “Maybe I’ll be a teacher. I’ve been thinking about that. Or a hair stylist. I don’t really know yet.”

One thing she does know is that graduating is key to even the most basic of her goals. “I am the first one to come out for school. My mom and my older sister dropped out when they were in high school,” she says. “I don’t think anyone in my family ever graduated.”

Despite their long separation, Ms. Aysanabee’s mother fully supports her life in Thunder Bay, and hope it brings her daughter closer to her dreams.

“She is proud of me,” says Ms. Aysanabee. “She was telling me over the March break that she wants me to do this for me.”

Madeleine White is a digital editor with Globe Video.

Editors’ Note: A previous version of this article incorrectly said that the bands served by Dennis Franklin Cromarty High School fund the school, and that aboriginals run its direction and administration. In fact, the Ministry of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development funds the school, and the indigenous community runs its direction and administration. And the story incorrectly said one student was found hanging from a tree with a noose made of Christmas lights around his neck; in fact, one graduate was found under those circumstances.