Did you know that Inuit ingenuity was behind the life jacket? Or that a Toronto mother invented a bouncy harness enjoyed by children all over the world? And the whoopee cushion? Yup, that impish idea came from a Canadian company.

In their new book, Ingenious: How Canadian Innovators Made the World Smarter, Smaller, Kinder, Safer, Healthier, Wealthier and Happier, Governor-General David Johnston and entrepreneur Tom Jenkins set out to educate a country of its illustrious innovation past with nearly 300 examples.

"We want that eight-year-old girl in Regina, who is thinking about starting a company, to be inspired by hearing a story of a similar young woman in New Brunswick doing something phenomenal," Mr. Jenkins said.

In addition to the book (whose proceeds go to the Rideau Hall Foundation), Mr. Jenkins and Mr. Johnston have also worked with a team to set up an online database that catalogues more than 2,000 Canadian innovations, write a children's book and co-ordinate a new curriculum module with teachers at Nippissing University to help motivate Canada's future innovators.

"There is such a wealth of these stories," Mr. Johnston said. "And people learn best by stories."

The selections in the book range from the life-saving (insulin) to the practical (the paint roller) to the quirky (the Sphynx cat). They also illustrate how the vast geography and variable weather of Canada helped spur an inventive, hardy spirit in Canadians.

"We really did create things that the rest of the world adopted," Mr. Jenkins said. "You can't help but be proud to be a Canadian."

The Governor-General firmly believes that much of Canadians' innovative spirit is "just under the surface" and hopes this book motivates people to indulge their curious and creative sides.

"I wanted to recognize the great possibility of Canada," Mr. Johnston said. "And how we can enhance the lives of all Canadians if we consciously all put our minds together to do things better, particularly better in a way that improves the human condition."

Aircraft Mass Production

The queen of the hurricanes

Elsie MacGill's life was one of firsts: the first woman in Canada to earn a degree in electrical engineering; first woman in the world to be awarded a master's degree in aeronautical engineering; first woman to design a plane; first woman to hold the position of chief of aeronautical engineering at an aircraft company; and the brains behind the world's first mass-produced aircraft. Soon after World War Two erupted in Europe, Elsie's Canadian Car and Foundry in what is now Thunder Bay, Ontario, was selected to manufacture the Hawker Hurricane for the Royal Air Force in 1939. Elsie swung into action. She took control of production, streamlined operations to churn out increasing numbers of aircraft, and even designed a series of modifications to equip the fighter for cold-weather flying. By 1943, the company had produced more than 1,400 Hurricanes and its workforce had grown from 500 to some 4,500 – more than half of them women. Elsie had devised and perfected the mass production of aircraft, a mode of production that was soon the norm worldwide. No wonder this Canadian woman of firsts was crowned "Queen of the Hurricanes."

Dendritic Cell

National Institutes of Health

The engine of adaptive immunity

"I know I have got to hold out for that. They don't give it to you if you have passed away. I have got to hold out for that." In the fall of 2011, Ralph Steinman was deathly ill with pancreatic cancer. The Canadian immunologist clung to life, awaiting word from Sweden on whether he would be awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine. In 1973, while working at Rockefeller University in New York, Dr. Steinman had discovered what he called dendritic cells. The cells are essential elements of the human immune system. Their main function is to process antigen material to make it present on the surface of a cell so that T cells can interact with the material. An antigen is a molecule capable of inducing an immune response on the part of a host organism. T cells are a subtype of white blood cells, which are central components of immunity in human beings. Since their discovery, dendritic cells have become known as the primary instigators of adaptive immunity and have been used to design vaccines to fight hiv and several forms of cancer. Alas, cancer claimed Dr. Steinman before he received word from Sweden. Fittingly, the Nobel committee granted him the award nonetheless. He had held out long enough.

Duck Decoy

Canadian Museum of History

The hunter's secret weapon

The hunter's most formidable weapon is deception. The Cree and Ojibway peoples of Canada's Great Lakes relied on it for thousands of years. They used reeds, cattails, bulrushes, tamarack, and other plants to make remarkably lifelike floating and stationary decoys that lured game birds and waterfowl to roosting areas. Once there, they were within reach of the nets, snares, arrows, and spears of the Aboriginal hunters. European settlers and then generations of recreational hunters wisely took up the practice for themselves – a deceptively simple technique that continues to this day in much the same way it has for thousands of years.

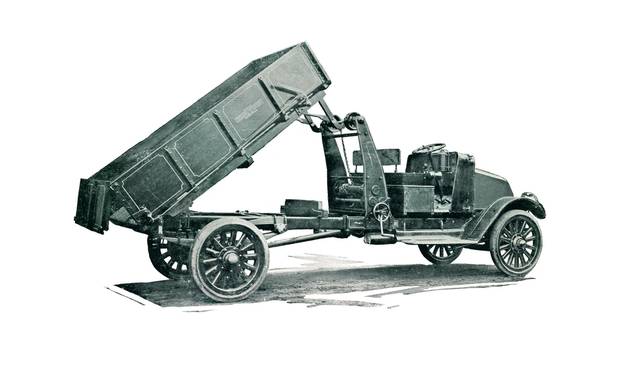

Dump truck

Canada Science and Technology Museums

The quick spill

Perhaps the greatest time-saver for the modern labourer is – of all things – the good ol' dump truck. Think about it. Instead of needing a group of strong backs to shovel a big load of dirt or gravel or whatever out of the box of a truck, the dump truck just, well, dumps it. Credit for the first one goes to Robert Mawhinney. In 1920, the Saint John New Brunswicker put together a truck equipped with a special dump box in back. The dump box was fitted with a mast, cable, and winch. A simple crank handle was used to operate the winch, which tugged on the cable that lifted the front end of the box high enough to dump its load out the open back. His idea was an instant hit; within a decade the dump truck was mandatory equipment wherever earth was moved. Shovels down, lads.

Forensic Pathology

RCMP Heritage Centre, Historical Collections Unit

Sherlock of Saskatchewan

Modern crime scene investigation methods did not appear first in Miami, New York City, Las Vegas, or even Scotland Yard. The originator of forensic pathology is a remarkable woman who worked on the Canadian Prairie. Dr. Frances McGill was the first person in the world to make this science a regular part of police investigations. Appointed Saskatchewan's chief pathologist in 1920, Dr. McGill travelled by any means necessary including dogsled and floatplane throughout the vast province to investigate suspicious deaths. Known as the Sherlock Holmes of Saskatchewan, she applied her training as a medical doctor to study crime scenes and protect and preserve evidence in ways that had never before been done. She also became renowned for her courtroom appearances, where her riveting and rigorous testimony – anchored in medical science – would exonerate the innocent and convict the guilty. And she taught what she knew and had learned – how to tell human blood from animal blood, for instance – to students at the Regina Police Academy. Today, those insights and methods either are still in use or have inspired others and are relied on by police departments across Canada and around the world. Even Miami.

Jolly Jumper

Courtesy of Jolly Jumper

The back saver

Life is hard enough with two arms. When one of them must hold a squirming youngster, it can be downright impossible. After her first child was born in 1910, Toronto mother Susan Olivia Poole was keen to stay active. Inspired by the papooses used by Aboriginal mothers to carry their children, she fashioned a harness of her own. It was a cotton diaper fashioned as a sling seat, a coiled spring to suspend its wearer from above, and an axe handle to secure the contraption. Susan called her combination a Jolly Jumper. As she worked in home and garden, her son bounced playfully and safely nearby in his new jumper, toes just off the ground. Susan had six more children and made Jolly Jumpers for each. When her children had children of their own, Grandma Susan made even more. In 1948, she began to build and sell them, eventually patenting her jumpers and selling them farther afield. Today, Susan's jolly little harnesses are no longer made out of diapers, springs, and axe handles, but they are all hard at work freeing the arms and saving the backs of countless grateful parents around the world.

Life Jacket

Shutterstock

The Inuit fisher's insurance

When exposed to Canada's frigid waters – both coastal and inland – you will often perish more quickly from heat loss than drowning. Inuit whale fishers knew this truth. They made what are known as spring-pelts, which are sealskin or seal gut stitched together to create a waterproof covering for their torsos. These early life jackets evolved, more insulated and buoyant over time, until they became the sailor's salvation we know today.

Paint Roller

Shutterstock

The do-it-yourselfer's blessing

Do-it-yourselfers around the world, take a moment of silence to honour Norman Breakey. In 1939, he created the first paint roller. Great idea. The roller applied paint evenly and made painting itself faster than ever. Yet the visionary Torontonian didn't patent the innovation – not the fabric-covered cylinder, nor the long pole shaped liked the number seven, nor the ridged pan made from tin. Big mistake. Knock-offs emerged quickly and others secured lucrative patents by making minor modifications to Norman's original idea. And what of Norman himself? Not much if anything is known of his fate. So before you paint that wall or ceiling, take a moment to remember him. No one else will.

Robertson Screwdriver

Canada Science and Technology Museums Corporation

The no-slip screw and driver

Peter Robertson cut his hand and changed an industry. The mishap occurred in 1908 in Montreal, when the Milton, Ontario, salesman for a Philadelphia tool company tried to demonstrate how to use a spring-loaded screwdriver to fasten slotted screws. Slotted screws – more commonly known by the surname of their creator, Henry Phillips – were notorious for not only causing screwdrivers to slip but also for being stripped themselves when fastened or unfastened. Once his hand healed, Peter got to work. The industry-changing device he came up with is a square-socket screw. The screw's chamfered edges, tapering sides, and pyramidal bottom meant it could be screwed in faster, easier, and tighter than Phillips's version. The eponymous Robertson was an immediate hit. Henry Ford, for one, insisted on using Robertson screws and screwdrivers when he learned that his automotive assembly lines could build each car two hours faster doing nothing different but using these new screws. Everyone wanted a piece of the action, but Peter wasn't willing to hand over control. As a result, the Robertson screw never became the universal phenomenon it deserved to be. That said, more than a century later the company that bears his name is still producing his superior patented screws for everyone who wants a safer, easier, tighter fit.

Walkie-Talkie

National Research Council of Canada

The point-to-point communicator

Donald Hings probably had little idea just how useful his creation was about to become. In 1937, the Canadian inventor created the first handheld portable two-way radio transceiver. Donald called it the packset. It soon gained widespread use and fame under a more descriptive name – the walkie-talkie. Within two years, war erupted in Europe and Donald was summoned to Ottawa to adapt his packset for military use. Thousands of the sturdy and reliable devices were soon in the hands of Allied infantrymen around the world. They became even more popular after the war. First responders relied on them as essential equipment. Truck drivers used them to report emergencies and stay in touch while on the road. Even kids were equipped with them, roaming around their neighbourhoods during the day and chatting under the covers at night when they should have been sleeping. 10-4. Roger out.

Whoopie Cushion

Andrew Paterson Alamy

The new sound of novelty

A new sound: that's all a novelty item needed to become a raging sensation in the late 1920s.Companies offered a wide variety of devices that emitted strange sounds when squeezed – some a child's scream, others a cat's screech. Experimenting with sheets of rubber, employees of the jem Rubber Company in Toronto hit upon a different sound. The noise that emanated from their little rubber pillow was a tad more, how shall we put it, indelicate. American novelty purveyor Johnson Smith & Company heard the call and added jem's doohickey to its giant catalogue. The economy model went for 25 cents, a deluxe edition for $1.25. A perfect gift for the discerning prankster who has everything. Sales erupted with a loud toot and haven't ceased. The sound of the Whoopee Cushion can still be heard loud and clear wherever unsuspecting bottoms and chairs get together.

Excerpted from Ingenious by David Johnston and Tom Jenkins. Copyright © 2017 David Johnston & Tom Jenkins. Published by Signal/McClelland & Stewart, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited. Reproduced by arrangement with the publisher. All rights reserved.