“How can a person who believes in Torah kill an innocent person?”

This is the question Benny Lau, the rabbi of the historic Ramban Synagogue in the Old City of Jerusalem, asked this week just before I arrived in the city.

There are other pressing issues to pursue here: Air raid sirens are wailing every day as Jerusalem is coming under unprecedented rocket attack. And as many as 40,000 reserve troops are being amassed from across the country for a possible ground invasion in Gaza.

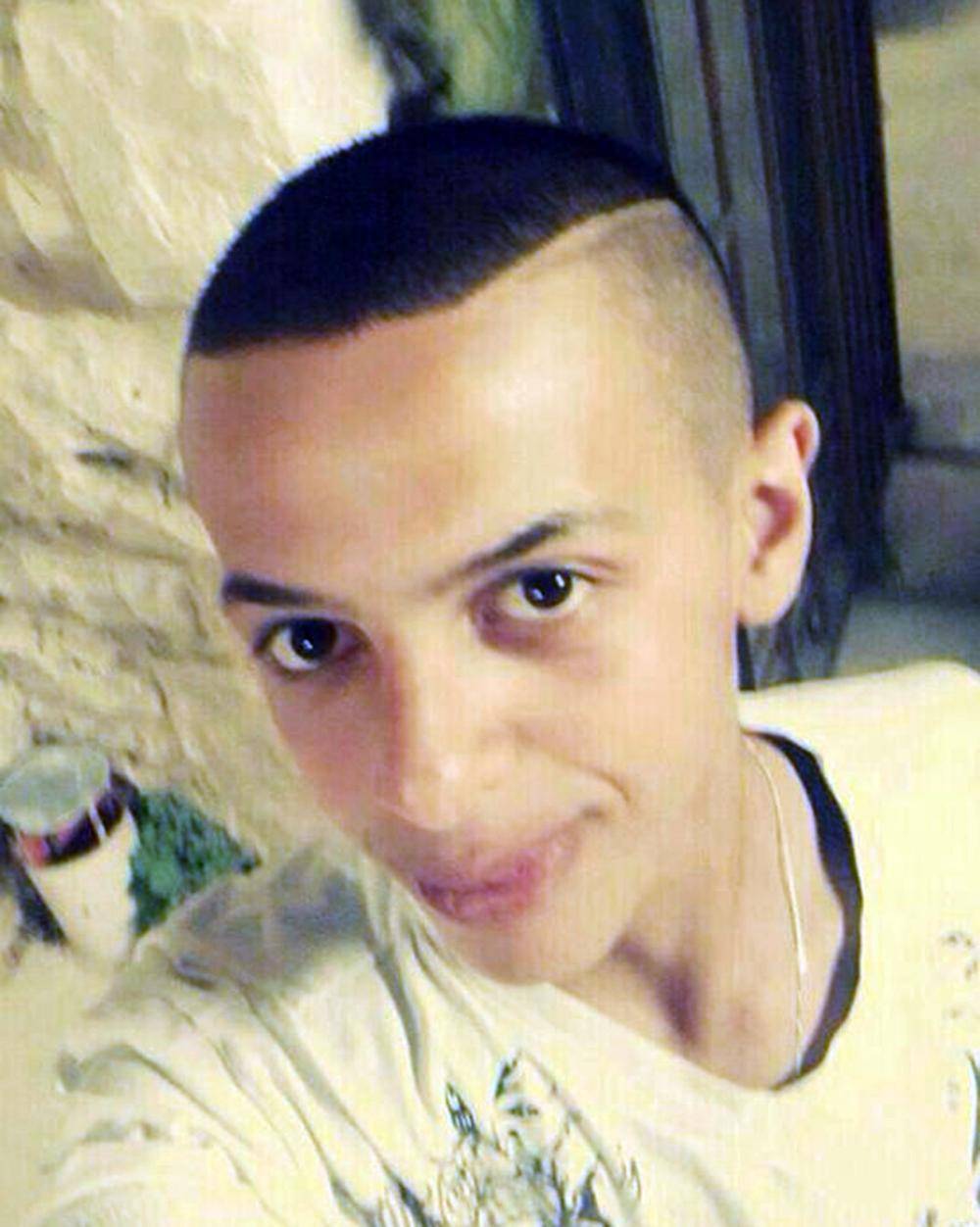

But every Israeli I speak to says they are haunted by the July 2 abduction and brutal slaying of 16-year-old Palestinian Mohammad Abu Khdeir.

His murder came just hours after the funeral of three Israeli teens who had been abducted and killed in the West Bank – which enraged Israelis, who still search for what many believe are their Palestinian killers.

Mohammad’s killing, though, shocked many. Partly because of its cruelty – he was abducted at 3:45 a.m. as he prepared for the ritual Ramadan meal before dawn, and was then burned alive – and partly because of who was allegedly behind it: young members of a Haredi, or ultra-Orthodox, family, out for revenge.

Jews everywhere were aghast. Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu denounced the killing as “terrorism” and vowed justice would be served. Hundreds of Israelis joined the funeral for the young Palestinian on Tuesday. Scores more continue to file into the mourning tent erected just beside the site where he was abducted.

But as further details emerge (a gag order has barred most news on the arrest), the killing points not to a one-off aberration, but to a growing problem. The alleged perpetrators don’t appear to be mainstream Haredim – they are believed to be disaffected ultra-Orthodox youth who are turning to violent politics for a sense of meaning and belonging.

“They flunked out of Yeshiva, don’t fit into traditional Haredi society, and they have difficulty fitting into secular society,” says Gershom Gorenburg, author of The End of Days: Fundamentalism and the Struggle for the Temple Mount.

Many remain out of public view, because Haredim do their own policing. But with an average of nine children per ultra-Orthodox family, their numbers are rapidly expanding.

The people apart

The Haredim – the term means “those who tremble” (in awe at the word of God) – regard themselves as the most religiously authentic of all Jews.

They have had a constant presence in Israel for more than two thousand years. But the majority of Haredim arrived in the 20th century; from Eastern Europe and the Arab world in the first half, and from the United States in the second.

Unlike Zionists, they did not come to create a Jewish state. They insist that Jews should not bother with such things but devote themselves to prayer and following the Torah. They reject both modernity and secular culture. Education is strictly religious; TV and the Internet are forbidden. Hassidic Jews, one branch of ultra-Orthodox Jews, even wear clothes like those worn in their European shtetls more than 200 years ago.

About one in 10 Israelis (more than 750,000 people) are now part of this ultra-Orthodox society. They tend to live in close-knit communities around their synagogues in larger cities. And at first, their desire for isolation meant they were largely absent from politics in Israel.

But a small group, Agudat Yisrael, worked with the Jewish Agency to bring Jews here after the Holocaust. In the 1980s, two more parties were launched to represent different branches of Haredim. All of them have since become comfortable players in both left- and right-wing governments. Their primary goal is their own interests. And when mainstream parties need a coalition, Haredim have worked with them to derive benefits for their communities in the form of higher welfare payments, or increased budgets for religious schools.

For many of the Haredim, life is certainly not easy. Many men spend their time at religious seminaries while women take care of large families and also work in sex-segregated jobs. That makes family resources tight. One report suggests half of working-age Haredi men are unemployed, and many accept government welfare.

Some Israelis resent this dependence, and the isolation of the Haredim. There have been recent efforts at integration: The Israeli government is gradually starting to draft Haredi men, limiting exemptions to military service to a much smaller number; there’s a quiet push to bring the country’s core curriculum (i.e. math and English) to Haredi schools; some entrepreneurs are reportedly hiring ultra-orthodox women for high-tech sector jobs (in sex-segregated offices).

But some young Haredim find themselves caught in the middle of all this, says Mr. Gorenburg. They aren’t suited to religious study. Yet they have no education, or cash, to pursue anything else. So, eerily like their Muslim counterparts, “they act like gangs,” he says, causing trouble.

These young men are also “particularly receptive to external political messages,” he says.

A ‘small leap’ to violence

On the day the funeral was held for the three Israeli teenagers killed in the West Bank, Michael Ben Ari, a former member of the banned Kach party who now leads Otzma LeYisrael (Strong Israel), was encouraging acts of revenge.

He posted reports on his Facebook page stating that Arabs were rioting in Jerusalem, had attacked a bus full of religious passengers and overwhelmed a group of border police who had been sent to the rescue.

He even used old photos showing a bleeding passenger beside an overturned bus.

None of it was true, yet 3,700 people “liked” his posts and more than 2,100 shared them.

He also drew hundreds of responses on Facebook from commenters cursing Arabs and describing their preferred method of dealing with them – shooting, slaughtering, burning.

On the streets of Jerusalem, Mr. Ben Ari whipped a crowd of young men into a frenzy. Many set off to hunt for Arabs, which was when Mr. Abu Khdeir was abducted and killed.

Disaffected Haredi youth, says Ami Ayalon, former head of the Israeli intelligence agency Shin Bet, “hear these calls for revenge and take it as permission to kill.”

But many observers also point to an acceptance of violence in Haredi society. “There was something in their upbringing that led them to believe such killing was justified,” says Hebrew University sociologist Nachman Ben-Yehuda of the alleged murderers of Mr. Khdeir.

In his book Theocratic Democracy, Mr. Ben-Yehuda notes the use of so-called “modesty patrols” – having made Israeli police feel unwelcome, Haredim patrol their own streets to guard against misbehaviour, using force to impose discipline.

More than that, extremist members of the community have often resorted to violence in an effort to rein in those who betray what they see as the true values of Judaism.

In the 1950s, for example, underground group Brit Hakanaim bombed and burnt Jewish shops that sold pork or “immoral” publications, and torched cars that were driven on the Sabbath. Similarly, young vigilantes in Haredi communities today, such as Beit Shemesh in central Israel, have been accused of breaking up young couples sitting too close together on park benches or busses. Their goal, Mr. Ben-Yehuda says, is to make a purer, and ultimately theocratic, state.

But if Haredi men – disaffected or not – grow up believing that secular Jews are “bad,” they are also taught that non-Jews are beyond the pale. “It’s only a small leap,” says Mr. Ben-Yehuda, “to targeting non-Jews” with violence, “especially Arabs,” who occupy sacred Israeli ground.

“The problem is that there’s chapter and verse [in the Bible] … in which aggression toward others is allowed, vengeance is celebrated, and revenge is celebrated,” says Rabbi Dr. Donniel Hartman, president of the Shalom Hartman Institute in Jerusalem, a pluralist research centre.

Yigal Amir, for example, the man who assassinated Yitzhak Rabin in 1995, cited scripture as his justification – he believed he was saving the Land of Israel from being spoiled by a peace agreement with the Palestinians.

Still, if some Haredim believed both non-observant Jews and non-Jews were “bad,” they didn’t tend to bother about Arabs – until now. Mr. Ayalon, who was made head of the Shin Bet following Mr. Rabin’s assassination, says “things are totally different today.” He’s seen “the growth of anti-Arab sentiment expressed within Haredi circles in recent years.”

Shmuel Eliyahu, chief rabbi of the northern Israeli city of Safed, is a vivid example: The city’s university had drawn Arab Israelis to study there, but Rabbi Eliyahu issued an edict directing Jewish landlords not to rent rooms to them.

His edict was controversial enough, but young Jewish men also took it as permission to act violently against Arabs in Safed. They broke the windows of their apartments and slashed the tires of their cars.

‘Things must be done differently’

Rabbi Eliyahu came by his hate honestly.

His father, Mordechai, started Brit Hakanim. He was imprisoned for 20 counts of violence against less Orthodox Jews, but he later became chief Sephardi rabbi of Israel – and in the 1990s started to integrate Haredim with the national-religious Jews who dominate the settlers’ movement in the West Bank.

They have important things in common, he taught. Primarily, the establishment of a theocracy.

That’s led to what Mr. Ben-Yehuda calls a “process of Haredization” among some settlers. But also the politicizing of some Haredim. In recent years, as Haredi politics has become more right-wing, and accommodation in Jerusalem more limited, large numbers of them have moved out to the West Bank, creating two of the biggest settlements there (Beitar Ilit and Modiin Ilit).

In these circles, notes Mr. Ben-Yehuda, Arabs are referred to as “Amalekites,” a hated foe of the ancient Jews, and one that in those times were targets for extermination.

The larger problem is that there are growing numbers of Haredim in Israel – and as some become radicalized that means a shift is underway: “Thirty years ago, [Israelis] were fighting for national goals,” says Mr. Ayalon. “Now it’s becoming a religious kind of war, and is likely have a much more negative outcome.”

After the murder of Mr. Khdeir, there was an immediate attempt to shut down religious rhetoric and to vilify any acts of vengeance.

In a newspaper piece this week, departing Israeli President Shimon Peres and his successor Reuvin Rivlin wrote: “A national struggle does not justify acts of terror. Acts of terror do not justify revenge. ... Even in the face of the rage and frustration, the violence and the pain, things can be done differently. Things must be done differently.”

But as Mr. Ben-Yehuda points out, little is being done to stamp out the incitement for such acts of terror, “And that’s a big mistake.”

There’s a concept in criminology, he says, called a “hotspot.” If a burglar or vandal breaks a window in some community, you better get it fixed. “If you don’t replace it, it will serve to encourage further criminal behaviour.”

In the same way, he says, “if the incitement isn’t stopped, more incidents such as this one will happen.”