Shimon Peres, the enigmatic Israeli politician who served his country as prime minister, president, defence and foreign minister, died Wednesday. He was 93.

Two things can be said with certainty about this study in contradictions: Mr. Peres, a Nobel Peace Prize winner, is remembered today mostly as a dove, a conciliatory leader, almost too eager, some would say, to make a deal with his country's Arab neighbours.

Obituary: Peres, guiding hand behind Israel-PLO peace pact, dies at 93

But what is much less well-known is that Mr. Peres, who never served a day in the Israeli army, did more than anyone to make the Jewish state a military power that could survive whatever the Arab world or any other enemy could throw at it. In the long run, it is that for which he will likely be most remembered.

Ironically, Mr. Peres, whom the late Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin once called an "incorrigible schemer," also planted seeds that would grow into perhaps the greatest long-term threat his country will ever face.

A bust of Mr. Peres, left, is seen next to other former Israeli presidents in the gardens at the Israeli presidential residence in Jerusalem.

AMIR COHEN/REUTERS

The arms dealer

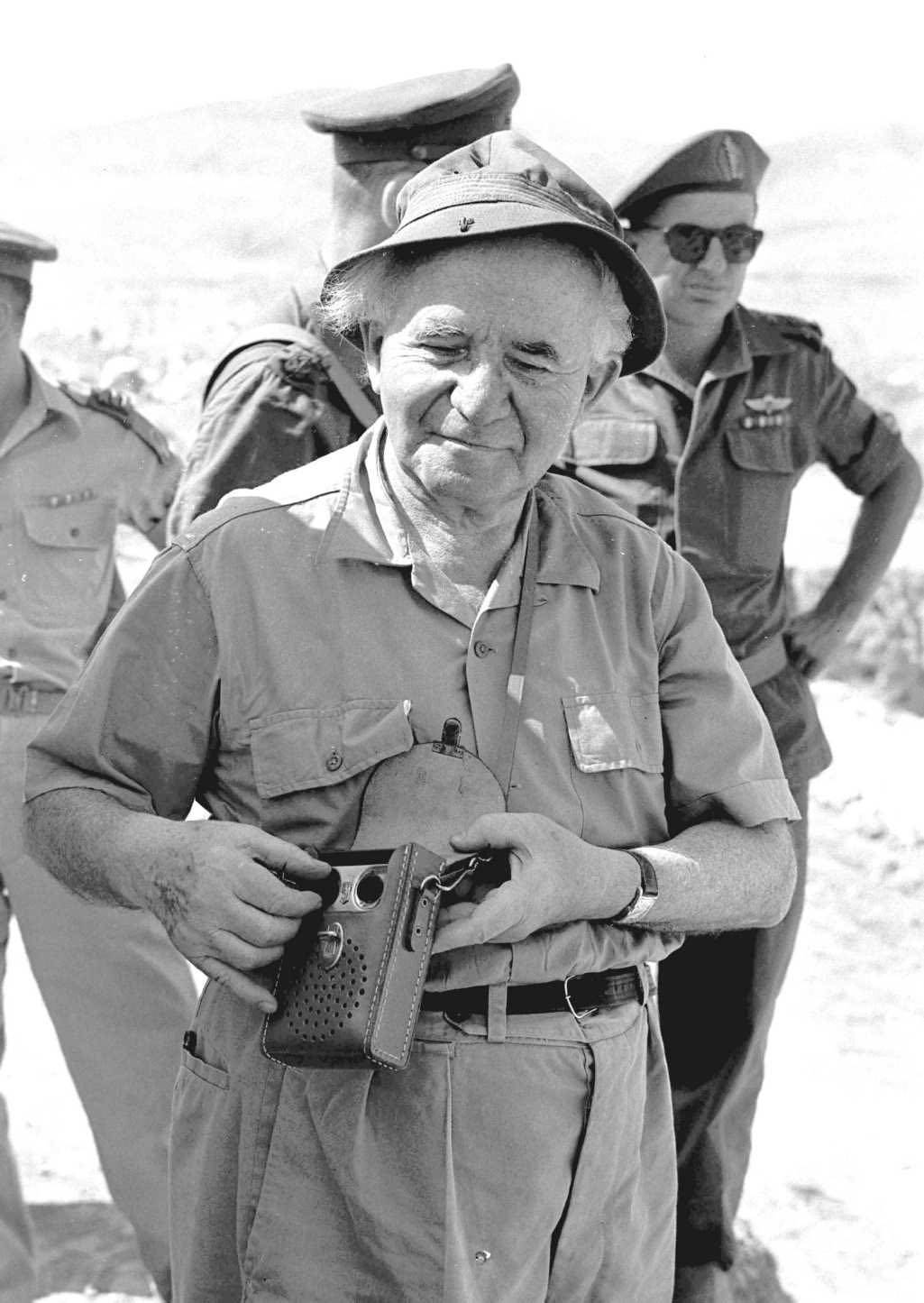

When Israel's founding father and first prime minister David Ben Gurion wanted to better equip the new state to defend itself, it was the young Shimon Peres to whom he turned. Throughout its battle for independence, Israel had fought mostly with weapons it made itself in small arms factories or ones it had captured from the British and from enemy Arab fighters, or purchased secretly from the former Czechoslovakia.

Mr. Peres succeeded in negotiating the purchase of surplus cannons from Canada in 1951 (despite an international arms embargo against weapon sales to Israel or to its Arab enemies) and even found a supportive Jewish Canadian, Sam Bronfman, to pay for them.

By the age of 24, Mr. Peres had been named head of Israel's fledgling navy and by 29, he was deputy director general and then director general of the Defence Ministry. During those days from 1952 to 1959, he secured more arms from Eastern Europe and especially from France which sold him hundreds of tanks and scores of jet fighters. All the while he quietly fostered Israel's own arms industries that would in time turn out world-class small arms, tanks, rockets and fighter aircraft.

Regarded in those days as a "Ben-Gurionist" hard-liner or hawk, Mr. Peres had a penchant for secrecy. Few Israelis realized what he was up to throughout the 1950s.

For one thing, he worked closely with the French and British in orchestrating Israel's ill-fated attack on the Egyptian Sinai in 1956.

The operation was intended to secure the Suez Canal for the European allies, deliver territory in Sinai, including the Gaza Strip, to Israel and keep Egypt's ambitious president Gamal Abdel Nasser in his place. It failed when the United States called out the British and French for their secret plan and forced everyone to return to their original positions with a Canadian-conceived UN peacekeeping force separating the Egyptians and Israelis.

An Egyptian soldier surrenders to an Israeli army patrol in the Sinai Desert on Nov. 1, 1956.

ISRAELI GOVERNMENT PRESS OFFICE/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Israel's secret weapon

More significantly, it was Mr. Peres in the 1950s and 60s who developed Israel's capacity to produce nuclear weapons.

In his 1993 book, The New Middle East, he wrote: "What Israel really needs, I thought, is the strategic capability to deter or intimidate the enemy – to rid him of his desire for war."

With nuclear fuel and technology supplied by France, Mr. Peres established the Dimona nuclear facility in southern Israel. He wrote that it was "designed as a research institute, but in the eyes of neighbouring Arabs … became a worrisome, fuzzy deterrent."

Israel has never formally acknowledged that it has an arsenal of nuclear weapons, nor has it denied the allegation. As a result, it has served as an effective deterrent.

Mr. Peres noted that when, in the late 1970s, Egypt became the first Arab country to make peace with Israel, Egyptian officials privately admitted they did it in part because of worries about Dimona, and the nuclear capability it gave Israel.

In a 2010 interview with Israeli historian Benny Morris, Mr. Peres acknowledged that he even tried in May, 1967, to avert the coming war with Egypt and Syria by proposing "a certain measure" as a warning to Mr. Nasser not to start a war. The "certain measure" to which he referred is widely believed to have been the exploding of a nuclear bomb in the southern Negev desert.

The Israeli cabinet rejected such a show of force and launched a pre-emptive strike against Egypt instead, enabling Israel's speedy victory in the Six-Day War over Egypt, Syria and Jordan.

The widespread belief that Israel possesses nuclear weapons has led several people to question why Iran should be denied the right to develop its own. Mr. Peres has always been quick to answer.

In a 2012 interview with The Globe and Mail, he said "the world understands the difference. … They [the Iranians] want to destroy us."

Israel, Mr. Peres always insisted, will never be the first in the Middle East to use nuclear weapons.

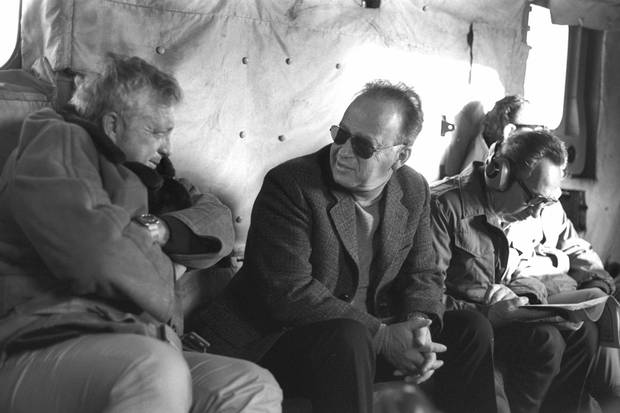

Mr. Peres, right, then the defence minister, sits next to prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, middle, and security adviser Ariel Sharon, left, on a military helicopter flight in 1975.

YAACOV SAAR/ISRAELI GOVERNMENT PRESS OFFICE/REUTERS

Settlements in Samaria

Shimon Peres was among the first in the Israeli leadership to promote the establishment of provocative Jewish settlements in the northern heart of the occupied West Bank, the area Israelis call Samaria. It happened in the mid-1970s when Yitzhak Rabin first became prime minister and Mr. Peres served as defence minister.

Previous governments had been quick enough to build Jewish settlements following the occupation of the West Bank in 1967, but only in certain areas: in the Jordan Valley, where they justified them as outposts along the border with Jordan, as well as near Bethlehem, where a substantial Jewish community had existed prior to the 1948-49 war, and in the southern Arab city of Hebron where a Jewish community had thrived for 3,000 years.

In 1974, however, in the wake of the near disastrous Yom Kippur War of 1973, a group of radical nationalist Jews calling themselves Gush Emunim (Bloc of the Faithful), aimed to take advantage of Israelis' desire for greater security by building new settlements throughout the occupied land of Samaria. The group had tried and failed to establish a "wildcat" settlement (done without government approval) during the Golda Meir administration, and made another attempt on the third day of the Rabin-Peres administration, which, they had reason to believe, would look more favourably on their enterprise.

Prime Minister Rabin called Gush Emunim "a cancer" and ordered their trailers and shacks removed. As defence minister, in charge of the West Bank occupation, Mr. Peres carried out the order but harboured support for the group that he saw as employing the same kind of tactics earlier Zionists had used to create facts on the ground that eventually would become the state of Israel.

Gershom Gorenberg in his book on Israel's settlements, The Accidental Empire, details how repeated efforts to establish settlements near the Arab city of Nablus were rebuffed, until Mr. Peres quietly allowed a group to set up facilities at an old railway station named Sebastia and alongside an army camp in a place the settlers called Ofra.

Reluctantly, Mr. Rabin agreed to allow them to stay, persuaded that it would be too heart-wrenching for Israelis to have their own army dragging Jews out of their homes. Those few dozen settlers have spread and multiplied over the years until they now number more than 300,000 (not including Israelis in areas near Jerusalem that also were captured in 1967).

Years later, Mr. Peres told Benny Morris he was not responsible for what happened in Samaria.

"It's a matter of proportions," he said. "I never agreed to 300,000 settlers. We were for settlements which were agricultural-military [not civilian settlements], like Ofra. That was the idea."

But in 1976, Mr. Peres had defended the right of Israelis to settle anywhere in the occupied territories. He told the Labour Party newspaper, Davar: "I don't understand why it's okay to settle in the [Jordan] Rift and not in the Samaria mountains. … I don't understand why settling in the Golan Heights [captured from Syria in 1967] is considered something left-wing and settling in Ofra next to Jerusalem is a right-wing act."

Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak meets with Mr. Peres, then Israel’s prime minister, in Alexandria on Sept. 11, 1986.

KHALED ABU SIEF/REUTERS

Cloak-and-dagger diplomacy

It was only in the 1980s that Shimon Peres rebranded himself as a dove. He had come to believe that, thanks to him, the country was militarily strong, that the peace treaty with Egypt assured it of security to the south, and that the next logical step was to work out some arrangement to deal with the Palestinian population of Gaza and the West Bank.

But he was far from wanting to see the creation of a Palestinian state.

Instead, as foreign minister in a national unity government with the right-wing Likud party, he turned to the kind of secret negotiations he liked best.

In 1987, he concluded a deal with Jordan's King Hussein for resolving the status of the West Bank. It was referred to as the London Agreement, having been negotiated in the office of an English doctor of whom both men were "patients."

The agreement was intended to restore much of the occupied West Bank to Jordanian control, along with all the Palestinians in it, while leaving the Israeli settlers mostly in place. The Palestinians would be given Jordanian citizenship and each West Banker, whether Palestinian or Israeli, would be able to vote for their own nation's parliament. A local West Bank legislature would be established to handle matters other than foreign and defence, and all West Bankers would participate in this limited administration.

The plan was torpedoed by then-Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Shamir, who didn't want to give up any of the territory.

It would be five more years before Mr. Peres would accept the idea of an independent Palestinian state (and even then, he believed, the state had to be demilitarized and have limited power in foreign affairs). Nor did Mr. Peres want to abandon the Israeli settlements in the West Bank. That notion too would have to wait, even as the settlements would continue to swell.

Mr. Peres, middle, the historic Oslo agreement at the White House on Sept. 13, 1993. Behind him are Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin, an unidentified aide, U.S. president Bill Clinton and PLO chairman Yasser Arafat.

J. DAVID AKE/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

When Labour returned to power in 1992 under Yitzhak Rabin, Mr. Peres, once again foreign minister, oversaw the clandestine Oslo talks between Israeli and Palestinian officials that led to the 1993 Oslo Accord and the Nobel Peace Prize he kept prominently displayed in his office.

But the accord fizzled, particularly after the 1995 assassination of Mr. Rabin and the advent of deadly suicide bombing attacks by Hamas, the Palestinians' Islamic Resistance Movement.

In 2005, Mr. Peres left the Labour movement after almost 60 years and joined Kadima, a new political party established by then-prime minister Ariel Sharon. Mr. Sharon, overcoming great internal opposition, had carried out the unilateral withdrawal of all Israeli forces and settlers in Gaza, an idea Mr. Peres had long advocated.

He became Kadima's nominee for president in 2007, winning that election on the second ballot.

Even in that largely ceremonial office, he was unwilling to let the chance for a peace deal slip away so he acted. He negotiated secretly again, this time with Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas, and reached a broad consensus.

The agreement, Mr. Peres later told Israeli television, was arrived at in four secret meetings in Jordan. It called for mutual recognition of "a Palestinian state" and "a Jewish state," the latter being a priority of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. The size of the Palestinian state was agreed on though the precise borders remained to be negotiated. There even was agreement on how to resolve the vexing refugee issue.

Mr. Netanyahu, however, stopped the deal at the last minute. Mr. Peres said he was perplexed as to why Mr. Netanyahu did this.

"I didn't conduct private negotiations," Mr. Peres insisted. "The Prime Minister was an accomplice to the negotiations at every step of the way."

For all the attention paid to Mr. Peres's peacemaking efforts, historian Benny Morris believed they took second place to his efforts for security. When all is said and done, Mr. Morris said of Mr. Peres in 2010, "beneath his polished, world-weary exterior, he is still the ex-defense minister who believes that for a stable Israel, security concerns must take the highest priority and that any chance of peace is ultimately contingent on Israel's strength."

Shimon Peres on July 6, 2014.

TSAFRIR ABAYOV/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Follow Patrick Martin on Twitter: @globepmartin

MIDDLE EAST: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Could this built-from-scratch city start a Palestinian renaissance? Take a tour of Rawabi

3:12