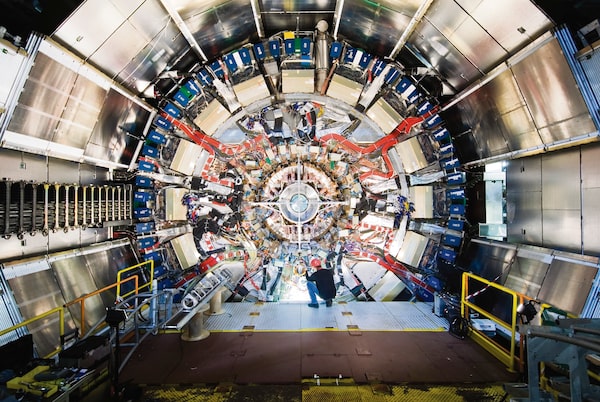

Scientists work on part of the massive ATLAS detector at the Large Hadron Collider during its initial installation in 2007.Claudia Marcelloni/Max Brice

Lawrence M. Krauss, a theoretical physicist, is president of the Origins Project Foundation and the host of The Origins Podcast. His most recent book is The Edge of Knowledge: Unsolved Mysteries of the Cosmos.

Science is, by its very nature, a deeply social endeavour. In the modern world, where the issues scientists are addressing have become both more complex and more weighty, the need to tap the intellectual resources of all of humankind has never been more important. But that has also opened science up to the growing threat of politicization, and the pressures that come with it.

The looming removal of Russian scientists from the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN)’s pioneering experiments at the Large Hadron Collider at the end of November, in response to Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, puts into stark relief the challenge that global geopolitics, and political ideology more generally, pose to the scientific enterprise.

In the near term, this is a disaster for a group of scientists who themselves bear no responsibility for the actions of their government. Indeed, thousands of Russian scientists signed a petition opposing the invasion shortly after it began. For many of them, their association with CERN has provided a lifeline that has allowed them to continue their research, and to educate the next generation of students in their home country.

I remember visiting Poland to deliver a lecture shortly after the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. There, I met a Polish physicist whose textbook I had admired. I was shocked to learn that his salary as a faculty member at his institution was insufficient to allow his family to survive. The only way he could continue to carry out research was by spending one month a year at CERN, which provided enough funding to allow him to continue leading his research group back home.

Because CERN’s decision to not renew its international co-operation agreement with Russia (and Belarus) was first announced two years ago, many of those scientists have been able to obtain positions outside of Russia so that they can continue their work. While this may solve their own personal issues, it does not address the deeper effect of essentially shutting off access to research in fundamental particle physics at their previous home institutions in Russia. A generation of talented young students will now lose the opportunity to follow their academic dreams, and the field will lose the chance to benefit from their potentially significant contributions.

The loss to science that arises from cutting off one group of people for political or ideological reasons is not purely hypothetical. In the case of CERN, it will immediately cause setbacks for continuing experiments. As Hannes Jung, a German physicist working on an experiment using the Large Hadron Collider, put it: “It will leave a hole. I think it’s an illusion to believe one can cover that very simply by other scientists.”

History is replete with examples of the negative consequences of restricting the scientific enterprise on the basis of political ideology. These range from the disastrous expunging of genetics researchers in Stalinist Russia led by Trofim Lysenko, which resulted in crop failures and subsequent starvation, to the arrests and expulsions of Jewish scientists in Nazi Germany, which removed Germany from the forefront of theoretical physics for decades (though this ultimately benefited the rest of Europe and the United States).

I recently heard a direct example of how political barriers to Russian scientists came close to holding back the progress of science in the field of cosmology, in which I have done much of my own work. When I interviewed renowned Russian cosmologist Andrei Linde, who now works at Stanford, for a recent podcast, he related how it was only the chance opportunity he once had to travel outside the Soviet Union for a physics conference that caused him to develop his seminal ideas on cosmic inflation, which he then published in a Western science journal. How many more young Russian scientists will lose the opportunity to make similar contributions if they are excluded from the global community of scientists?

What may be more worrisome about the CERN decision is that it is not being made in a political vacuum. The incursion of politics into academia is increasing in tandem with polarization in the West. There have been widespread calls to boycott Israeli academics and their institutions because of the conflict in Gaza, even though many of them have also opposed their own government’s policies; that has not mattered to the hundreds of professors in the U.S. and abroad who signed petitions to support such a boycott. Even the American Association of University Professors, which has for decades worked to support academic freedom by categorically opposing academic boycotts, recently announced a policy change that sets out that boycotts of institutions “are not in themselves violations of academic freedom and can instead be legitimate tactical responses to conditions that are fundamentally incompatible with the mission of higher education.”

Once the international academic community goes after one country for one reason or another, what is to stop it from ferreting out others? Will American scientists be excluded from international collaborations because of the U.S. government’s support of Israel, or because of various past ignominious efforts to overthrow sovereign governments, including its own past insidious efforts in Ukraine?

Science is, or should be, apolitical by its very nature: The universe is the way it is, whether we like it or not, and whether or not it conforms to our own views of what may be just. The effort to interrogate nature to find out how the universe works, and the consequent development of technologies that have benefited all of humanity, must in turn be independent of ideology. While scientists themselves are not free of biases, the scientific process itself ensures that ultimately those biases don’t hold sway. Science transcends individual scientists, be they good or bad, atheist or religious, Russian or American. It does this by ensuring a healthy dialectic. No idea is sacred or immune from attack, and the results from experiments – not national sovereignty or political strength – should ultimately adjudicate between competing theories.

Once the floodgates holding back ideological pressures have been opened, such that national origin or political beliefs become a litmus test for participation in the scientific enterprise, the progress of science and scholarship in general is threatened. We are witnessing such dangerous trends in the West already, where, for example, defending biological notions such as the binary nature of sex can lead to academic, and social, cancellation.

Academic freedom is essential, not because academics are special, but because societal progress is held back whenever such freedoms disappear. The scientific enterprise in the 21st century is inherently international. The internet has levelled the playing field in a wonderful way, allowing young scientists from around the world to have unparalleled access to cutting-edge research.

In this way, science can unify humanity in ways that few other intellectual activities can. There is no Western science, or Eastern science, or Russian science, or NATO science – there is only the universal language of science. Scientists from scores of countries speaking dozens of languages, worshipping their own gods and having potentially conflicting political beliefs, speak and understand the same precise mathematical language of science without translation problems or vague misinterpretations. They can work together to break down not just the barriers that nature puts in the way of understanding, but also the ones created by national and international boundaries.

Large CERN experiments such as the Compact Muon Solenoid require work from thousands of scientists, representing every gender, nationality, race, size and shape of human. That is a heartening testament to what is best about the human species: how awe and wonder can unite us to pursue challenges we would otherwise never dream of conquering. When we introduce artificial political divisions that exclude some people from the enterprise, in the end we all suffer.