This is an excerpt from A Nation’s Paper: The Globe and Mail in the Life of Canada, a collection of history essays from Globe writers past and present, coming this fall from Signal/McClelland & Stewart.

“The subject who is truly loyal to the Chief Magistrate will neither advise nor submit to arbitrary measures – Junius.”

Those words first appeared on the front page of the first edition of The Globe, on March 5, 1844, and they’ve been in the paper ever since, now on the editorial page. Junius is, and always has been, the notional author of the newspaper’s unsigned editorials.

George Brown chose those words, and that author, because they spoke to his beliefs about the dividing line between legitimate government and illegitimate rule. The original Junius was an 18th-century British Whig who wrote under a pseudonym to avoid winding up in court, or jail, for his broadsides against the British government of the day, and what he saw as its abuse of power against the rights of Parliament and people. In Canada, where the burning issue of 1844 was whether the country would get responsible government – government accountable to Parliament – Junius’s dictum must have struck Brown as particularly apt.

The governor-general of the Province of Canada at the time, Sir Charles Metcalfe, was attempting to govern without the support of the majority in the colony’s legislature. For Brown, it meant that the Crown’s representative in Canada was claiming powers that the Crown in Britain had long ago surrendered to Parliament. However, Upper Canada’s Tories were supportive of the governor, and he of them. They accused opponents of being radicals and revolutionaries, disloyal to Canada and Britain.

Brown would become famous for his editorials (many, in fact, penned by his younger brother, Gordon), which bulldozed opponents with a torrent of logic, facts and, often, mockery. But before he published his first Globe editorial, he came up with an editorial motto whose meaning readers would have grasped instantly, at least in 1844.

Brown used the original Junius’s words to say that if anyone was loyal, it was Junius of The Globe – and if anyone was disloyal, it was the governor and the Tories. Ruling without the support of the representatives of the people was unconstitutional in Britain, so how could it be desirable in British North America? The subject who was truly loyal would not consent to arbitrary government, nor would he advise the Crown to govern arbitrarily. Yet arbitrary government is what the governor and the Tories were advising and practising. In such circumstances, what was true loyalty? Opposition.

“Let me exhort and conjure you,” the original Junius had warned readers in 1772, “never to suffer an invasion of your political constitution, however minute the instance may appear, to pass by, without a determined, persevering resistance.” He said the best protection against such invasions was a free press – “the palladium of all the civil, political and religious rights.” That made newspapering, and editorial writing, not just a business for Brown, but a high calling.

In the years before Confederation, Junius became Upper Canada’s leading voice for free trade with the United States (but firmly against talk of annexation); British-style parliamentary government (but not American-style Jacksonian democracy, with its elected upper house and elected judges); separation of church and state (opposed by Anglicans and Catholics); representation by population (opposed by Quebec, which feared the growing English-speaking majority); and joining the Atlantic provinces, British Columbia and the vast territories of the Hudson’s Bay Company to Canada (ditto).

Junius had big dreams, but Canada’s two decades before Confederation were marked by political paralysis, because of seemingly irreconcilable “racial” differences between French and English. Some said separation was the answer; Junius called that “the advice of the coward.” Separation would landlock Ontario and “place our foreign commerce at the mercy of Brother Jonathan” – an earlier personification for Uncle Sam – “and Jean Baptiste.” And a divided Canada, lacking “the strength to command respect,” risked being swallowed by the U.S.

“To be a great state, we must continue our alliance with Lower Canada,” insisted Junius. But how? The answer Junius came to embrace was federalism. Federalism made Confederation possible.

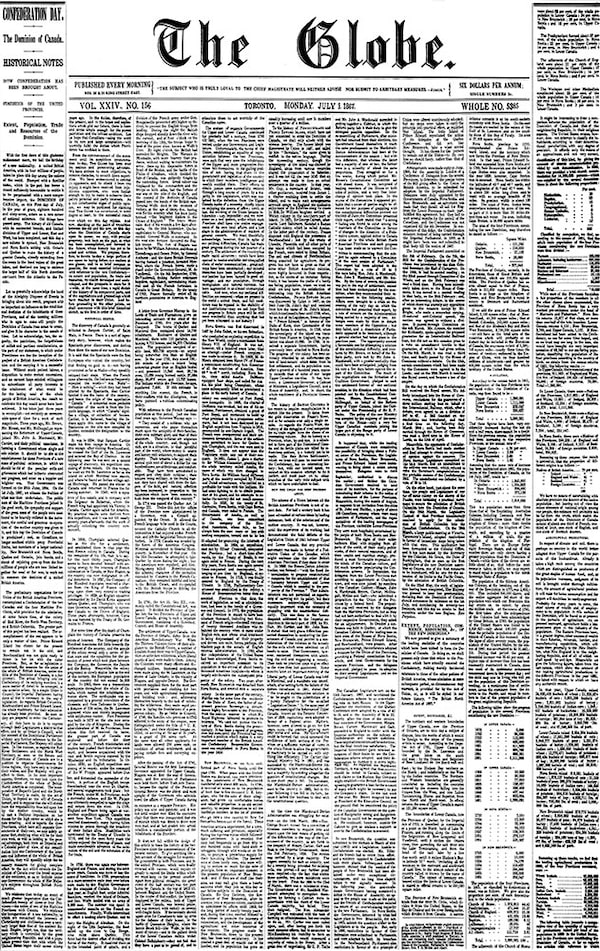

The Globe's edition from July 1, 1867, was largely a paean to the country Brown had just helped to create.

On July 1, 1867, Junius celebrated the new Dominion of Canada. The editorial was the only thing on the front page, and its nine columns of dense type consumed page 2 and turned to page 3. In 9,000 words, written by Brown himself, Junius laid out Canada’s possibilities – which, in a particularly Canadian move, he saw in America’s reflection.

The Dominion Day editorial offered a compendium of comparisons between the infant America of 1776 and a nascent Canada in 1867. The United States had gone from fragile experiment to continent-spanning colossus – could not Canada do the same? Canada already had “a population greater than that with which the United States began their career ninety years ago,” and like the U.S. could one day extend all the way to the Pacific. Junius saw a future of “teeming millions who in ages to come will people the Dominion of Canada from ocean to ocean.”

In the run-up to Confederation, Junius and Brown alienated French Canadians and Catholics with strident calls for secular schools and rep-by-pop, yet they also learned to compromise, even on big issues, in pursuit of the larger goal of a greater country. And for the next century and a half, keeping that country whole, by balancing competing desires across the sectional divide, remained top of mind for Junius. Sometimes Junius found the balance. Sometimes not.

On the North-West Rebellion of 1885, Junius was sympathetic to the plight of the Métis, arguing that the Conservative government of Sir John A. Macdonald had ignored their legitimate claims, year after year, leaving them no choice but to take up arms. With Louis Riel on trial, the headline on a July 27, 1885, editorial was: “One criminal tried by a greater.” On Oct. 7: “Blame the real criminal.” And on Oct. 24, after Riel was sentenced to hang, Junius wrote: “The responsibility for the rebellion, and for all the bloodshed in the North-West, rests upon SIR JOHN MACDONALD.” Junius called the prime minister “the first criminal in this case” and “the greatest criminal, because his cold-blooded criminality was the cause of all the crimes of all these unfortunate Metis.”

Attacking Macdonald and the Conservatives was par for the course for The Globe of that era, for it was not just a liberal paper, but a Liberal paper. Nevertheless, these were remarkably strong words, and many readers would not have appreciated them. Junius took a position in line with that of most French Canadians – who were outraged by the treatment of the mostly francophone and Catholic Métis – but against majority opinion in mostly Protestant English Canada, particularly in deeply Orange Toronto.

Junius wasn’t always so solicitous of the francophone minority. When Ontario brought in Regulation 17, forcing French speakers to go to school mostly in English, Junius was supportive. In an editorial on Feb. 26, 1916, Junius said that Le Devoir founder Henri Bourassa, by demanding “the principle of equality of rights for both races all over the land,” was trying to create “a racial cleavage.” Junius argued that forcing French children into English classrooms was for their own good. “Quebec is likely to be bilingual for all time but Ontario is firmly resolved to maintain English as the official language.”

The Red Ensign, then Canada's flag, flies outside the Canadian embassy in Washington in 1944.National Film Board of Canada

Liberal MPs cheer and sing O Canada in 1965 after raising the new maple-leaf flag.The Canadian Press

By the early 1960s, Junius worried that “Canada must surely be the first nation in history that courted elimination because its citizens could not work up the interest to keep it alive.” Junius wondered if Canadians might be “perfectly willing to submerge their Canadianhood in the great nation to the south, and add a few more stars to Old Glory in place of the Canadian flag they never got around to creating.”

But as for that new flag, Junius was opposed. He called prime minister Lester Pearson’s push to replace the Red Ensign “a silly issue” that risked igniting conflict. When the conflict caught fire, Junius was not surprised: The prime minister had “chosen to press the divisive issue of a national flag at a time when emotions are already deeply stirred by the question of national unity – or rather, by the lack of unity.”

Through the winter and spring of 1964, Junius urged Pearson to drop the flag business. Then, as the debate reached a peak, Junius reversed position. Recognizing the danger of an unbridgeable gap being opened between French and English, Junius asked the opposition Conservatives, and no doubt many Globe readers, to make a gesture of reconciliation and back a new flag.

Why? Because “they must concede that they have no real alternative to a flag designed around the maple leaf. French-speaking Canada can no more be persuaded to accept a flag in which the Union Jack is the dominant symbol than English-speaking Canada could be persuaded to acknowledge a flag in which the fleur-de-lis was pre-eminent … if we have to choose a flag at this time – and the Government is forcing the choice – we must look for a symbol that is offensive to none and acceptable to all.”

Junius also weighed in as Canada fought two era-defining federal elections on free trade with the United States, in 1911 and 1988. In both, Junius backed free trade as economically beneficial. In both, the opposition attacked free trade as an assault on Canada’s essence.

In 1911, the Conservatives argued that the soul of Canada – which for many Canadians of that era meant Britishness and the imperial connection – would be undone by free trade. Rudyard Kipling, in a letter published in The Montreal Star, argued that “it is her own soul that Canada risks.” Junius disagreed, but Junius’s side lost.

Anti-free-trade protesters greet Brian Mulroney as he heads to a televised federal election debate in 1988.John McNeill/The Globe and Mail

Three-quarters of a century later, Britishness was no longer part of the catechism of sacred Canadianess, but the claim that the nation’s immortal soul was in peril was still central to the anti-free-trade campaign, now led by the Liberals. Four days before the vote, on Nov. 17, 1988, Junius wrote:

“We had thought, perhaps naively, that the debate would turn on economic matters – benefits and losses under free trade (for of course there will be some of both), the quality of future jobs, the consequences for different regions and the like. Instead, Canadians listening to the debate have been told that their medicare system will be destroyed … Frightened old people have been told their pensions are at risk … Radioactive waste will be dumped in Saskatchewan, and on and on.

“All these things are possible in an imperfect world, of course – so are floods, killer bees and the heartbreak of psoriasis – but none will be caused by the free-trade agreement. John Turner, Ed Broadbent, hysterical editorialists and the plaster saints of our cultural world have a lot to answer for here.”

But the plaster saints did not carry the day. Junius celebrated, and highlighted what would not change: “The Conservative victory does not, however, transform Canada into a Thatcherite or Reaganite society. Canada has its own dynamics which put a premium on consensus, a feeling of community and concern for those in need. These values are deeply rooted and entirely consistent with a vigorous market economy.”

For more than 16 years, I was Junius, or a Junius, as an editorial writer from 1991 to 1999 and the editorials editor – Junius inter pares? – from 2013 to 2022. Writing an editorial – they run about 700 words these days – is as much about what you say as what you leave out. The latter is the hardest part. In this essay, I have of necessity left out much.

I don’t want to go without mentioning Junius’s most famous turn of phrase – that the state has “no right or duty to creep into the bedrooms of the nation” – which Pierre Trudeau lifted, edited and improved to: “There’s no place for the state in the bedrooms of the nation.” Or how Junius backed conscription in both world wars, which was in line with military necessity and the wishes of most voters in English Canada, but put near-fatal strains on national unity. Or how a sincere liberalism had Junius favouring alcohol prohibition in the early 20th century, but backing marijuana legalization in the 21st century.

And then there’s the fact that early Junius, though a moderate in most things, was a radical who brooked no compromises when it came to slavery. In 1849, he urged Canadians to welcome escaped slaves from the U.S. because, though Canada was poor, “we are possessed of a jewel more valuable than all the riches in the world, and that we present to many a poor and wearied fellow man – the jewel of freedom. These treasures we can give without limit.”

Reading through 180 years of editorials, I’ve been struck by how often history repeats and rhymes, and how events separated by generations often trod well-worn paths that, for Junius, raised recurring concerns.

Consider the invocation of the War Measures Act in 1970, and the use of the Emergencies Act in 2022. I was in Junius’s chair for the latter, and when I went back and read The Globe’s editorials from the fall of 1970, I discovered that an earlier Junius had wrestled with the same questions, gone through a similar thought process and reached similar conclusions.

Soldiers walk alongside Quebec provincial police headquarters in Montreal on Oct. 18, 1970, during the October Crisis.The Canadian Press

After Front de libération du Québec terrorists kidnapped James Cross in 1970, Junius urged the Pierre Trudeau government to safeguard public figures and public order. The FLQ had been carrying out terror bombings for years, and documents had earlier been discovered showing plans for a kidnapping campaign. Why had Ottawa not acted sooner, and why was it not moving more forcefully to uphold the law?

Junius took a similar position in 2022 with regard to blockades at the borders: Of course they were illegal, and government and police had to put an end to them. “Protest is a legal right,” said the headline of the Feb. 4 editorial, “but a blockade isn’t a legal protest.” Junius has often been that Canadian paradox, the law-and-order liberal.

But when Ottawa in 1970 went from inaction to the most drastic action – invoking the War Measures Act – Junius had reservations. “Only if we can believe that the Government has evidence that the FLQ is strong enough and sufficiently armed to escalate the violence that it has spawned for seven years now,” wrote Junius on Oct. 17, the day after invocation, “only if we can believe that it is virulent enough to infect other areas of society, only then can the Government’s assumption of incredible powers be tolerated.” Junius extended the government some initial benefit of the doubt, but day by day raised the degree of doubt.

Police climb over a snowbank to clear downtown Ottawa of protesters on Feb. 19, 2022.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

In 2022, Junius similarly questioned whether the government was overreacting and abusing the law. “The Parliament Hill park-in has been a long, loud, illegal imposition on Ottawa residents,” said the editorial of Feb. 16. “But a bunch of parked vehicles and drivers in hot tubs is not exactly an existential threat to the country.”

Two days later, Junius asked: “If COVID-19 didn’t clear the bar for the Emergencies Act, does this?” After three days more, pointing to the dubious suspension of habeas corpus in 1970, Junius described the freezing of bank accounts in 2022 as “a suspension of financial habeas corpus. Is that constitutional? Is it something Canadians want?”

The words on the masthead, already old when George Brown borrowed them, are still fresh.

Tony Keller is a columnist for Report on Business.

The Globe and Mail

The Globe at 180: More reading

CEO Andrew Saunders: After 180 years, our promise – journalism that matters – is unchanged

In A Nation’s Paper, journalists explore how The Globe and Canada evolved together

How George Brown helped create Canada in spite of himself

John Willison and Wilfrid Laurier, the dynamic duo of ‘sunny ways’

Meet the queens of the Gilded Age who pioneered women’s journalism in Canada

How Globe coverage of crime and punishment has righted wrongs and made mistakes

How The Globe changed its outlook on Africville, the razing and the racism