Nelson Mandela greets supporters as he walks with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney after arriving in Ottawa for a three-day visit to Canada on June 17, 1990.Wm. DeKay/The Canadian Press

Brian Mulroney fought to isolate South Africa’s apartheid regime and took a stand against white-minority rule at a time when many other Western governments were “wavering” on the issue, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa said.

Mr. Ramaphosa paid tribute to the former Canadian prime minister on Friday, lauding him for pushing for sanctions against apartheid in the mid-1980s.

“Prime Minister Mulroney led Canada during a critical decade in which our struggle for freedom culminated in the dismantling of apartheid,” Mr. Ramaphosa said in a statement.

“For us, his passing is made profound by the fact that we have lost this friend and ally in the year in which we are marking 30 years of freedom and in which we pay tribute to all those around the world who supported our struggle for freedom and democracy,” he said.

The South African government gave one of its most prestigious awards to Mr. Mulroney in 2015. He was appointed as a gold member of the Order of the Companions of O.R. Tambo – the country’s highest honour for foreign citizens – for his “exceptional contribution to the liberation movement of South Africa.”

In 1985, barely a year after taking office as prime minister, Mr. Mulroney helped lead a campaign in the Commonwealth to threaten sanctions against the apartheid regime, aiming to pressure it to abandon apartheid and release Nelson Mandela from prison.

This put him on a collision course with Britain’s then-prime minister Margaret Thatcher, who denounced sanctions as “immoral” and “utterly repugnant.” Over the next two years, Mr. Mulroney and Mrs. Thatcher clashed repeatedly on the issue.

At a Commonwealth summit in Nassau in October, 1985, Mr. Mulroney warned that Canada could sever relations with South Africa if apartheid was not dismantled. He played a key role in securing the Nassau Accord, in which the Commonwealth said it would consider “economic measures” against South Africa within six months if there was no progress in removing apartheid.

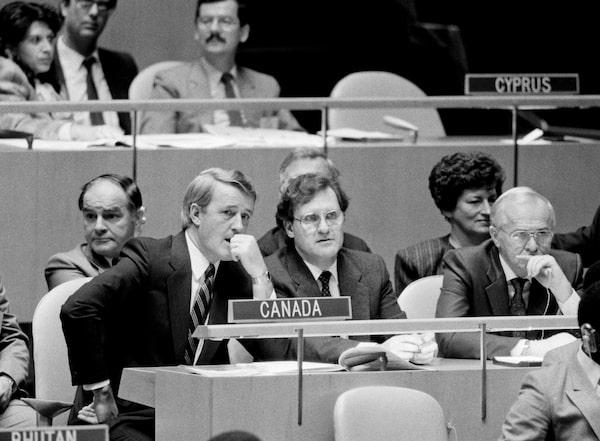

Just days later, Mr. Mulroney gave a powerful speech to the United Nations General Assembly, declaring that Canada was “prepared to invoke total sanctions” against the “repressive regime” in South Africa if apartheid continued.

Brian Mulroney, left, with his delegation shortly before his address to the 47th plenary meeting of the United Nations General Assembly on Oct. 23, 1985.UN Photo/Yutaka Nagata/UN PHOTO

“Only one country has established colour as the hallmark of systemic inequality and repression,” he said in the speech. “This institutionalized contempt for justice and dignity desecrates international standards of morality and arouses universal revulsion.”

In July, 1986, he argued fiercely with Mrs. Thatcher about the sanctions issue. He later described it as “one of the stormiest meetings I’ve ever been party to.”

In his memoirs, Mr. Mulroney said he often heard Mrs. Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, then president of the United States, denouncing Mr. Mandela and other anti-apartheid leaders as “communists.” He said his answer to them was always the same: “‘How can you or anyone else know that?... He’s been in prison for 20 years and nobody knows that, for the simple reason no one has talked to him – including you.”

In August, 1986, Canada and five other Commonwealth countries announced 11 new sanctions against South Africa, including bans on tourism promotion, new investment and air links, along with a ban on imports of South African coal, metals and agricultural goods.

Mr. Mulroney continued to push for sanctions, battling again with Mrs. Thatcher in a 1987 Commonwealth meeting in Vancouver. “I’ll never forget the way he went after Margaret Thatcher … with all the African leadership in the room,” said Stephen Lewis, who was Canada’s ambassador to the UN at the time.

“It was scathing, unforgiving and memorable,” he told The Globe and Mail in 2015. “I don’t think Thatcher had ever received such a tongue-lashing in her entire political life. I loved it. So did everyone else.”

Mr. Lewis said he is convinced that Mr. Mulroney played a “decisive role” in defeating apartheid. “He genuinely thought it one of the most evil systems on the planet. He had a real feeling for Mandela, and desperately wanted him out of jail, understanding that with Mandela’s freedom came South Africa’s liberation.”

During his visit to South Africa to receive the government’s award, Mr. Mulroney recalled how he had faced opposition from some MPs in his own caucus who accused Mr. Mandela of being a terrorist. “I had to persuade them that we were doing the right thing,” he told The Globe.

Scholars have noted, however, that Mr. Mulroney’s focus on the apartheid issue seemed to fade significantly after 1987 as he became preoccupied with domestic issues such as free trade negotiations.

“Overall, Canadian sanctions were quite modest,” said Linda Freeman, a Canadian political scientist who has written extensively on Canada’s relations with South Africa during apartheid. “And the important ones were voluntary,” she added, referring to financial sanctions.

She told The Globe that Canada’s trade with South Africa “remained substantial” during the sanctions period from 1986 to 1993.